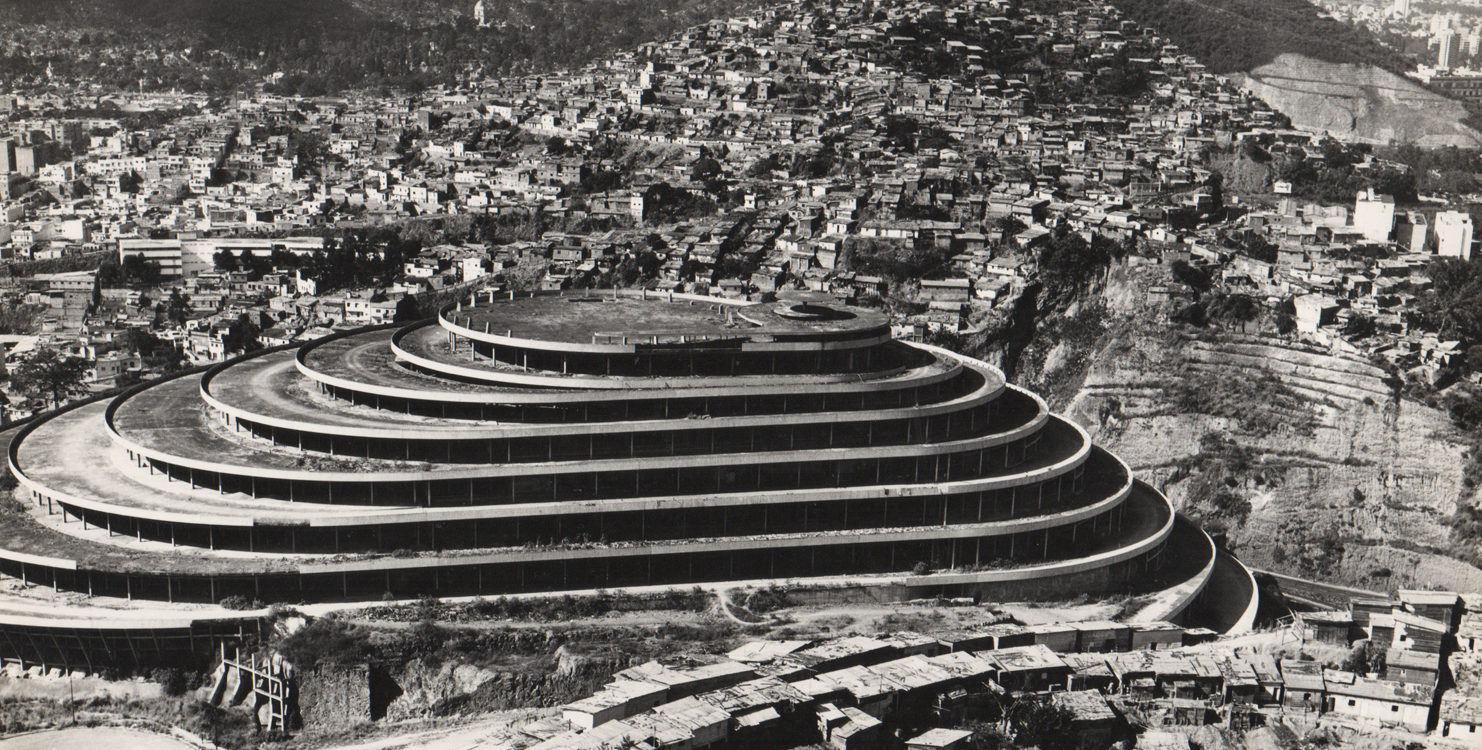

Beached cruise ship, fallen flying saucer, futuristic ruin; sitting amid the slums of San Agustín, in south-central Caracas, El Helicoide de la Roca Tarpeya looks different from every angle. So too do the many stories that haunt this construction, all as convoluted as its magnificent, double-spiral coils. Like its Babylonian inspiration, El Helicoide too was an ambitious project stopped short, in its case by the less-than-divine designs of politics. Like its famous predecessor, this concrete building—constructed in 1960 as a drive-in mall, the only one of its kind, where drivers could spiral up and down, parking right in front of the business of their choice—was halted shortly before completion. It was then abandoned to a fate that included oblivion and decay; multiple failed governmental projects; occupation by squatters and intelligence police; and episodes of drugs, sex, and torture; all sources for an endless number of legends, each more fascinating than the last.

In the 1950s, the combination of thirty years of oil revenues and a dictator, General Marcos Pérez Jiménez, bent on modernizing Caracas, made Venezuela into a haven for foreign architects. Some, like Graziano Gasparini or Federico Beckhoff, came looking for new opportunities and adopted the city as their permanent home. Others, including Gio Ponti and Oscar Niemeyer, visited briefly and were taken by the city’s modern orientation. The former contributed the famous “Villa Planchart,” kept intact as a 1950s icon to this day; the latter proposed a huge inverted triangle for the city’s museum of modern art, a project that was never executed. A few collaborated with local counterparts to design one-of-a-kind buildings. This was the case with Marcel Breuer and Herbert Berckhard, who partnered with Ernesto Fuenmayor and Manuel Sayago on “El Recreo,” a business and commercial complex that was also never realized, and with Dirk Bornhorst and Pedro Neuberger, two young German-born Venezuelan architects who were taken under the wing of Jorge (“Yoyo”) Romero Gutiérrez to help build modern Caracas. “There is so much to do,” Romero Gutiérrez would say. “Everything is possible.”

And so they set to the task, joining the likes of Carlos Villanueva, whose Universidad Central de Venezuela, which boasts a modernist campus with fluid lines and integrated art (including works by Léger, Arp, Vasarely, and Calder), was declared a World Cultural Heritage site by UNESCO in 2000; the daring Fruto Vivas, whose splendid auditorium shell covering El Club Táchira is a prime example of organic architecture; or Tomás José Sanabria, designer of the cylindrical mountain hotel El Humboldt, named after the German explorer who witnessed a meteor shower on a visit to the country in 1799.

In 1955, Romero Gutiérrez firm, Arquitectura y Urbanismo, landed a juicy deal. The owner of La Roca Tarpeya, a 328,000 square-foot hill, wanted to build a series of small apartment buildings accessible via a steep street. Romero Gutiérrez and his partners devised an alternative plan, changing the original idea from a residential to a more lucrative commercial development, and proposing a street that would spiral upwards, the roof of the premises below acting as a platform for the lanes above—a more economical and efficient use of the available space. The street eventually became a two-and-a-half-mile road, with alternating ascending and descending levels that comprise two interlocking spirals that resemble the genetic double helix. One thousand parking spaces, two for each business in the complex, would line the way.

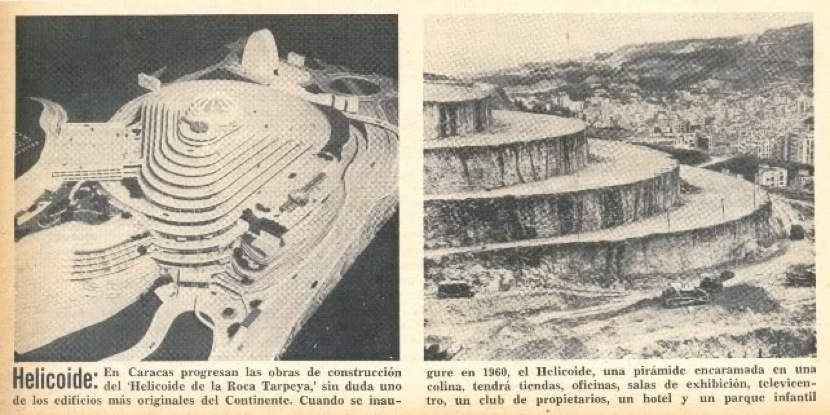

A modern shopping mall, “El Helicoide: Centro Comercial y Exposición de Industrias,” was designed to include large exhibition halls for the burgeoning national industries (oil, gas, iron, aluminum, agriculture); an automobile showroom; a gym and swimming pool; restaurants; nurseries; discotheques; a giant cinema; a first-rate hotel in which all the major airlines had offices; a heliport to fly passengers to and from the airport; and a full system of internal access with diagonal elevators and mechanical stairs. At its summit, under a dome designed by Buckminster Fuller, visitors could purchase souvenirs. The landscaping was to be designed by Roberto Burle Marx. El Helicoide was state-of-the-art, even by US standards.

“The whole construction,” as Bornhorst, its sole surviving architect, writes in his book El Helicoide, “was conceived as an artistic urban sculpture, an architectural pièce de résistance, smoothly adapted to the rhythm of the surrounding hills, itself forming another rise within the urban topography” in the valley of Caracas, whose hills made the architects dream of creating a tropical Acropolis. The budget for the 436,000-square-foot reinforced-concrete development was set at $10 million. By the time it was abandoned, costs had reached $24 million.

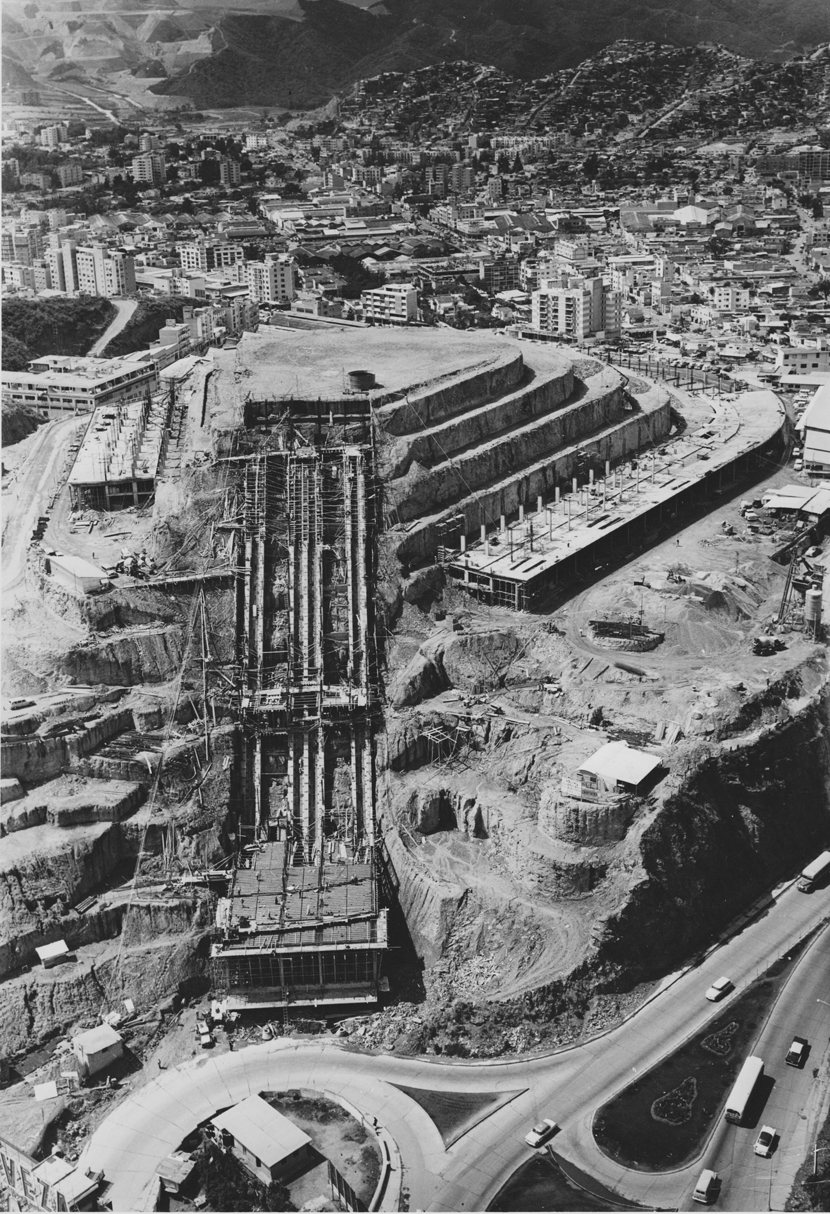

The model was inaugurated at the architects’ headquarters, the Centro Profesional del Este, in September 1955 with Pérez Jiménez in attendance, a questionable alliance whose extent is yet to be determined but which would eventually cost the project its life. Soon after, the colossal effort to raise the coiling tower began, with a plan as extreme as its shape: La Roca Tarpeya was sculpted inch by inch in order to fit El Helicoide hand in glove. This strategy dramatically constrained the building, as El Helicoide is literally sandwiched between the hill and the building’s enveloping road, providing no more than twenty-two to fifty feet of usable depth.

El Helicoide was an instant hit, its shape and scale attracting the attention of architects worldwide. Photos of the model appeared on the front page of foreign newspapers and occupied a prominent place at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1961 “Roads” exhibition. (El Helicoide is also set to appear in the museum’s spring 2015 retrospective on modern Latin American architecture). Back home in Venezuela, an advertising campaign to pre-sell the commercial spaces for the different businesses the building would house (an innovative form of raising capital at the time) produced drinking glasses, stickers, and key chains. Hoping El Helicoide would catalyze the urban development of southern Caracas, a boulevard connecting the building to the Botanical Gardens (next to Villanueva’s recently inaugurated Universidad Central de Venezuela ) was planned. The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote that El Helicoide was “one of the most exquisite creations ever to have sprung from the mind of an architect.” Salvador Dalí offered to decorate it with his art.

And then it all came to a halt—a slow, gradual halt that took everybody by surprise and from which El Helicoide never recovered. In January 1958, Marcos Pérez Jiménez was overthrown. Contrary to popular belief, El Helicoide was still not under construction, since only the custom-carving of La Roca Tarpeya had taken place between 1957 and 1958. Construction actually began in October 1958, under the provisional military government of Wolfgang Larrazábal, which oversaw the transition to democracy and allowed the building to go forward as long as its developers hired a large number of unemployed workers, part of a national emergency plan. They did, and El Helicoide roared on with 1,500 men working in three shifts round the clock for the next year and a half.

It was democracy that dealt El Helicoide its fatal blow. How exactly this happened is still unclear. Some blame the newly formed government of Rómulo Betancourt, which, unwilling to continue and thus legitimate the dictatorship’s massive urban renewal of Caracas, put conditions on a line of credit that had previously been granted to El Helicoide. The company balked, embarking on a lengthy legal dispute that would end only in 1976 when the empty building became state property. Others, including Pedro Neuberger, state that following Pérez Jiménez’s ousting, the main shareholders of El Helicoide (IVECA, a company owned by Roberto Capriles) fled the country, leaving the building financially adrift. In any event, contractors were not paid, and the business owners who had bought into the project sued the construction company, which went bankrupt. End of story for El Helicoide, the mall.

During the next twenty years, the construction that had made international headlines stood in almost total silence. Its architects despaired over their fantastic venture gone sour and turned to other projects. True to its modern temperament, always looking forward and never back, Caracas moved on, forgetting its magnificent spiral to consumer heaven. To their credit, local governments attempted to save the frozen giant. One after another, administration after administration proposed different commercial, cultural, and commercial-cultural plans, twenty-seven in total: automobile center, performance center, museum of art, tourism center, modern cemetery, center of radio and television, multi-cinema, national library, museum of anthropology, and environmental center, to name a few.

Of these, only the last two actually got under way, giving some life to the building’s empty halls—if we don’t count the massive occupation by squatters from 1979 to 1982, that is. Spurred by the official relocation of five hundred landslide refugees in El Helicoide in 1979, small groups began to install themselves in the building. By 1982, the unfinished structure was home to some twelve thousand squatters, all living without basic services in an economically depressed part of town. The building became a zone for trafficking in drugs and sex, with attendant high crime rates. This situation was literally washed away with hydraulic force in 1982 to open the way for the Museum of Anthropology.

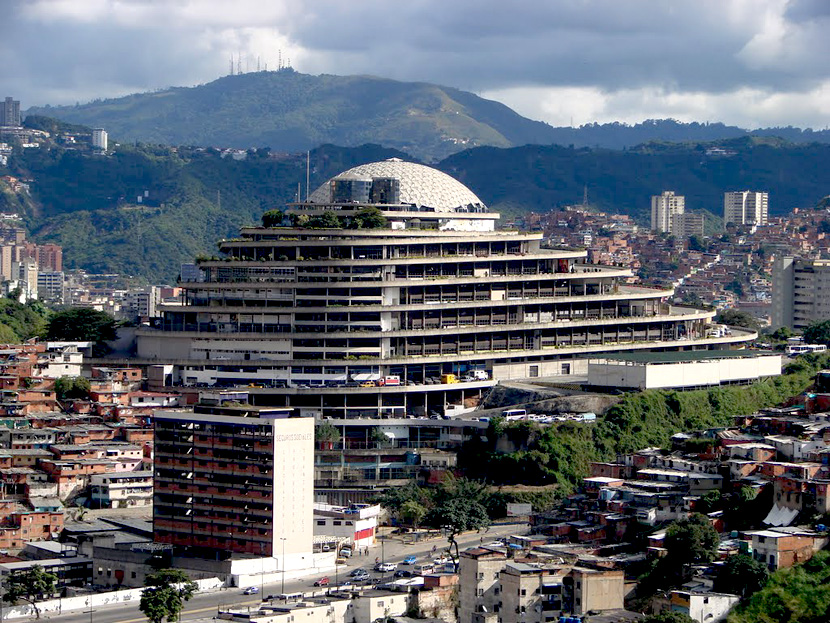

The Museum of Anthropology plan managed to finally place on the complex’s roof the Buckminster Fuller dome, which had been stored for over twenty years at a local warehouse. It didn’t get much further, despite having enlisted the collaboration of El Helicoide’s main original architect, Romero Gutiérrez (who, refusing to set foot in it again, counseled from a distance). The four high-tech Austrian Wertheim elevators, for example—each capable of carrying thirty-two people and designed to move diagonally on a thirtysix degree incline along the hill’s slope at a speed of 6.6 feet per second—were found at Venezuela’s main port, La Guaira, languishing away incomplete. They had arrived with great fanfare two decades earlier, but by 1982, very few people even remembered what those enormous machines actually were.

Soon after the museum plans were abandoned, another type of occupant began to install itself. Starting in 1984, the Venezuelan intelligence police (then DISIP, now SEBIN) gradually began to establish its headquarters in El Helicoide, the perfect panopticon with a 360-degree view of Caracas. A new kind of darkness set upon the building, this time arising from its conversion into a detention center. High-tech surveillance equipment was installed, officers delighted to be able to ride their cars to their offices à la James Bond. There were political prisoners, there was torture; SWAT teams would stop anyone taking a picture of the building from the surrounding highways.

Some believe the place is cursed. (The hill, after all, was named for Rome’s Tarpeian Rock, from which the daughter of the Roman general Tarpeius was thrown after being killed for betraying the city to the Sabines.) In 1992, for example, Julio Coll and Jorge Castillo, architects of the most progressive of the projects imagined for El Helicoide—the Centro Ambiental de Venezuela, designed to house the ministry of the environment, a laudably early response in the region to an underrecognized global problem—sought to dispel the negative energy that they thought might have been blocking the building’s progress. The duo took several measures to address its bad vibes, starting with a meditation under the Fuller dome during which they claimed to have heard voices informing them that an indigenous cemetery on La Roca Tarpeya had been disturbed during the construction of the building. Coll and Castillo’s project was completed in 1993, a magnificent headquarters that included a library with marble niches on the building’s top level. All to no avail—the Centro Ambiental was never inaugurated, and within a few months a new government had appropriated its glowing headquarters for the senior commanders of the DISIP. La Roca Tarpeya had struck again.

A few years later, the DISIP was joined by training schools for the police and the military, namely the Universidad Nacional Experimental de la Seguridad (UNES) and the Universidad Nacional Experimental de las Fuerzas Armadas (UNEFA). So proud of El Helicoide that it featured the building in a 2007 philatelic commemoration, DISIP was rebuked in June 2012 by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which determined that its detention center was in breach of international prison conventions on hygiene. A serious bacterial outbreak a year later finally led to the transfer of prisoners to other facilities, but the center still houses short-term detainees. The irony is staggering: a place that was meant to be a highway to consumer heaven became instead a stairway to hell, as if the spiral had spun downward instead of upward, opening the way for El Helicoide’s particular twist on its sacred referent, the Babylonian ziggurat. After all, the ziggurat is meant to connect the earth not only with the heavens above but also with the ground beneath. El Helicoide: a tropical ziggurat gone astray.

Rumors have it that El Helicoide has subterranean tunnels reaching out to different parts of the city. Like a rhizomatic helix whose coils spread waste and disillusionment, the slums around it have multiplied, as has the security apparatus that emerges from its entrails. The former grow so close to the building that they morph topographically with its curves; the latter use the building as a launch pad for their operations. A surreal platform, El Helicoide is as unexpected, unpredictable, and unique as Caracas’s ever-changing physiognomy.

For most caraqueños, El Helicoide is simply a part of the landscape, one of the many unfinished or abandoned buildings that add to the city’s irregular topography and unwieldy urbanism. For others, it is a reminder of the 1950s and 1960s, when Caracas underwent its modern boom, expanding in all senses. It was a utopian time that some remember with deep-felt nostalgia, whether for the dictatorial regime that gave the city its modern infrastructure or for the burgeoning democracy that immediately took its place after decades of quasi-consecutive dictators, each one stamping his own distinctive character on the fertile valley that once housed coffee and tobacco haciendas.

In the four decades after the discovery of oil in 1918, Caracas went from a quiet, semi-rural town of 140,000 inhabitants to an effervescent capital of the Americas with a population of more than 1.2 million and filled with highways, skyscrapers, and also schools for the families of employees of foreign oil companies (Shell, Mobil, Exxon) that were busily pumping Venezuelan oil. Like that oil, democracy gushed into existence, young and full of projects, eager to embrace a modernity for which Venezuela finally seemed ripe, ready to catch up with a world it had long admired. However, as with many other nations, Venezuela built its democratic dream on the back of a vast majority that it rarely saw, and acknowledged even less. The “fabulous party,” as Venezuelans themselves call the period from the 1940s through the 1970s, came to its final end in 1999 with the rise of the Bolivarian Revolution headed by Hugo Chávez. But the party had finished long before, and if anything, El Helicoide is the best testament to the extremes that have led Venezuela by the nose, swinging from despair to excitement and back again.

Modernity is a tricky condition, especially in countries like Venezuela, whose oil-driven emergence from a semi-feudal economy was nothing short of radical, and where catching up was not the same as growing up or becoming independent as a nation. On the contrary, catching up meant becoming if not equal, at least comparable, to its complicated northern neighbor, the United States. It meant being able to emulate the North American model, understood as the model of the future, of progress based on the paradigms of capital investment and mechanical efficiency. It meant, in a typically Venezuelan manner, beating the “gringos” at their own game: for example, building a supermall that would leave them stunned.

And so it did. In their essay for MoMA’s “Roads” catalogue, Bernard Rudofsky and Arthur Drexler make the point that El Helicoide’s “adventurous enterprise has been undertaken in Latin America and not in the United States, where both highways and shopping centers are among our most ambitious efforts.” Nelson Rockefeller tried to buy El Helicoide, but even he couldn’t overcome the legal quagmire that paralyzed the building until the state intervened and took it over. El Helicoide was a feat of the imagination and of technology, yes, but in a context where such things are secondary, where continuity is non-existent and maintenance considered a waste of time, and where purpose falls prey to a proprietary politics that binds the country to its leaders in a perverse filiation.

In the end, El Helicoide stands for exactly the opposite of what it was built to be. Instead of a dynamic center of exchange that might have revitalized the area and its surroundings, the building grew melancholically inward, fated, like an obsessive thought, to repeat its failure over and over again. Rather than expansive, it became sinister, a threatening fortress of “law and order” in a country that endemically ignores both. The building that could have become a symbol of modernity’s progressive thrust became instead an emblem of its failures—of the price paid for wishing to change everything at all costs, for imposing a vision unilaterally, for dreaming for others what they may not want to dream at all. As such, many think that in its ruined condition, El Helicoide offers the most appropriate portrait of a dystopic Caracas.

For the last thirty years, El Helicoide has been like a black sun, radiating inconspicuous state control, detention, and surveillance. For some, this fate might seem better than its lying in derelict abandon, yet it is far, very far, from the grandiose aspirations that fueled its original construction. And farther away still from the sacred geometry underlying pyramids and temples, the spiral dance at the origin of life and of these unique structures. Like them, El Helicoide, literally carved in stone, will outlast centuries of human history, even nuclear blasts. It will remain an icon of a future that never quite made it to the present.

This article has been published in issue #52 of Cabinet and was written by Celeste Olalquiaga. She is the director of Proyecto Helicoide, an ‘independent initiative which aims to culturally evaluate El Helicoide de la Roca Tarpeya, its structure, history and memory, through a series of exhibitions, publications and educational activities’.