The word ‘habitat’ has its origins in the Latin verb ‘habitare’: to live, inhabit, dwell. A basic part of everyday life, more than the sum of its translated parts. An activity common to all human beings. In its noun form, ‘habitat’ functions as a context for ‘habitare’, as the space where living, inhabiting, and dwelling take place. The human habitat, scaling conceptually from the individual dwelling all the way up to the planet Earth (and speculatively even further) implies simultaneously the quotidian and the complex. It encompasses aspects of everyday life at the local scale plus social, economic, and environmental aspects at the global scale.

Therefore, we might expect a conference and organisation named Habitat to consider all aspects of the space of ‘habitare’, critically approaching each scale from the human perspective. While met to some degree at the first Habitat conference of 1976, this expectation was nearly extinguished in favor of neoliberal policies at the second conference in 1996. The third conference, which recently concluded in Quito, unsurprisingly neglected the people who would stand to benefit most from an international conference on human settlements. This year’s celebratory agreement, the so-called New Urban Agenda, offers no alternative to the neoliberal policies that have resulted in massive expulsions worldwide. Instead, it reinforces the global economy’s tendency toward brutalities by way of leaving it unchallenged.

Vancouver and its Legacy

The first Habitat conference, fully titled the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements, was held in Vancouver in 1976. It resulted in the Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements and 64 recommendations for national action, which the UN General Assembly urged its member states to consider when reviewing their policies and strategies in the field of human settlements. This contribution to the UN system was made two years before Habitat’s establishment in 1978 as the UN Centre for Human Settlements (now the UN Human Settlements Programme, or simply UN–Habitat). Today, the program is coordinated by the greater UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), which oversees a variety of programs dealing with international economic and social issues.

For several reasons, which have been analysed in depth by Felicity D. Scott in Outlaw Territories, the debates at first Habitat conference became unintentionally political in nature. The UN debates were influenced by increasing radicalisation and overt politicisation from actors in the Third World, who supported the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s (PLO) attempt to gain visibility as a group affected by the national–political, not merely technological aspects of human settlements. This politicisation is reflected in the Vancouver Declaration, which explicitly recognises ‘that the problems of human settlements are not isolated from the social and economic development of countries and that they cannot be set apart from existing unjust international economic relations’.

Following the inclusion of the right to housing in the UN’s 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Vancouver Declaration furthermore recognises adequate shelter and services as a basic human right. It also states that it is of ‘paramount importance’ that national and international efforts give priority to improving the rural habitat, whereby disparities between rural and urban areas should be reduced to achieve a harmonious development of human settlements. It recognises urbanisation as a process in direct relationship with the greater environment, whose deterioration compels people to migrate to cities. Without this link, the economic causes for the emergence and growth of cities, whose development also affects rural populations, become invisible.

Following in the tradition of the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm four years earlier, the Habitat conference in Vancouver also offered a parallel space for civil society: Habitat Forum. It was located at Jericho Beach, away from the official conference downtown, where it made use of abandoned Canadian Air Force seaplane hangars. It was managed by the UN-appointed NGO Committee for Habitat, whose organisers worked, according to Scott, to ensure that its message remained on script by favoring business, professional, and prominent humanitarian and environmental groups over groups of citizens or those with political or activist tendencies. Habitat Forum functioned as a site for controlled dissent away from the honorable delegates.

It was organised around the trope of ‘unsettlement’ with an insistence that technical and managerial strategies could be deployed to replace politics as the domain of action, an insistence that Scott says sought to bolster a development paradigm in the interests of global capital. Even so, the meetings in Vancouver invoked the formation of new institutions and networks dealing with planning’s increasingly important role. Habitat Forum sparked, for example, the formation of the Habitat International Council (now the Habitat International Coalition, or HIC), whose mission remains the defense, promotion, and realisation of human rights related to housing in both rural and urban areas. These organisations would become the custodians of an alternative approach to human settlements centered on human rights.

In the 40 years since Habitat I, it has been proven difficult, if not impossible, to realise the explicit and implicit ambitions of the Vancouver Declaration within the scope of formal planning systems. Meanwhile, civil society groups have closely followed international political developments with Vancouver’s original vision in mind. One participant of the first Habitat Forum, architect and former HIC president Enrique Ortiz Flores, chronicled the uphill struggle to maintain and achieve the proposals made in 1976.

While many social actors continued working toward the proposals agreed upon in Vancouver, Ortiz Flores witnessed their gradual abandonment by the governments of wealthier (and more powerful) nations. According to Ortiz Flores, by the 1990s, the Washington Consensus, a set of neoliberal policy prescriptions designed inevitably to enable corporate expansion in developing countries, had effectively turned housing from its status as a human right into a globally tradeable asset or commodity subject the rules of the market. He lists the consequences of these policies: increasing poverty, exclusion, and inequality, the devastation of nature, and the cancellation of support for participatory habitat production — even its criminalisation and eradication.

At the second Habitat conference in Istanbul, in a reversal from the first conference, it became impossible through consensus to establish the immediate causes of the world’s ever-growing habitat problem. Lacking a ‘people’s forum’, as in the first Habitat, all deliberations were confined to the official proceedings. While negotiating the commissioned agreements — a general statement of principles and commitments plus a new action plan for the next two decades — a strong resistance to the principles set in Vancouver surfaced. Already at the second preparatory committee session leading up to the conference, as Ortiz Flores remembers, the United States delegation and some other countries actively rejected the further recognition of housing as a basic human right, which forced non-governmental actors to focus their activities on something that was thought already secured 20 years prior.

This right was, after extensive lobbying, finally maintained by governments and official delegations in the Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements and Habitat Agenda by reaffirming their ‘commitment to the full and progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing as provided for in international instruments’, placing emphasis on security of tenure, protection from discrimination, and equal access for all persons and their families. Yet, following Habitat II, few countries showed serious interest in realising these new commitments, many of them dissolving their local committees intended to follow up on them despite official UN–Habitat recommendations. As of today, the Habitat Agenda from Istanbul has not been fully realised, a fact that places the basic effectiveness of UN–Habitat under warranted scrutiny.

The New Urban Agenda

Despite the failure of the Istanbul Declaration, a third Habitat conference convened this October in Quito. Attending governments signed the voluntary, non-binding Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All (better known as the New Urban Agenda), which is intended to be seen as an extension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, many oriented toward cities and towns) and a reaffirmation of the Istanbul Declaration. Yet the ‘shared vision’ in the New Urban Agenda is unabashedly near-sighted: with its sprawling sentences, locked into a post-political jargon of worn out buzzwords and empty signifiers, the New Urban Agenda offers nothing new for the future of cities (or human settlements in general).

Instead, the New Urban Agenda reproduces the same economic relations that have, especially since the financial crisis of 2007–08, proven to be a devastating planetary force. Rather than reflecting on the failures of neoliberalism, which stopped the two preceding declarations from gaining traction, the New Urban Agenda appeals to corporations to strive toward sustainability, reminding us that ‘a stable international financial system’ is essential for human settlements. Furthermore, by almost exclusively discussing cities, the New Urban Agenda seems to forget that even as urban populations skyrocket, so will rural populations — not to mention city dwellers’ material dependence on them. Human flourishing in cities would be impossible without diverse extractive processes that take place in rural areas.

There may in fact be unspoken reasons for giving priority to urban development, sustainable or not, that trace back to the origins of the city. In Rebel Cities, David Harvey argues that since their inception cities have been a class phenomenon, because they arose through the geographical and social concentration of a surplus product. ‘Capitalism rests, as Marx tells us, upon the perpetual search for surplus value (profit). But to produce surplus value capitalists have to produce a surplus product. This means that capitalism is perpetually producing the surplus product that urbanisation requires. The reverse relation also holds. Capitalism needs urbanisation to absorb the surplus products it perpetually produces. In this way an inner connection emerges between the development of capitalism and urbanisation. Hardly surprisingly, therefore, the logistical curves of growth of capitalist output over time are broadly paralleled by the logistical curves of urbanisation of the world’s population.’

Urbanisation has thus played a crucial role in absorbing capital gains at the expense of violent processes of ‘creative destruction’ that dispossess the urban masses from any kind of right to the city. And the political answer to these processes of dispossession, by analogy with transformations in the fiscal system, is bound to be more complex today than in previous struggles. What, then should oppositional movements organising around the right to the city demand? According to Harvey, the answer is simple: greater democratic control over the production and use of the surplus, some of which was historically taxed away by the state before neoliberalism reoriented governments toward the privatisation of control over the surplus. Without envisioning a concrete alternative to neoliberalism, the New Urban Agenda effectively endorses its accelerated processes of dispossession in the financialised era and forecloses the possibility of any real right to the city. In this regard, there is nothing ‘new’ about the New Urban Agenda.

While the first Habitat conference may have established a preemptively emancipatory agenda, whose principles centered on the basic human right to adequate housing, it has become clear that Habitat’s original aims are unlikely be reached within the frame of the UN–Habitat program. HIC, in their public statement on Habitat III, claims ‘we need a New Habitat Agenda (not merely a new ‘urban’ agenda) that recognises the continuum of human habitat experience, respecting and securing multiple forms of housing and land tenure, where partnerships prioritise people and the public interest and states support the social production of habitat’. Such a habitat agenda will likely not emerge from official processes, at least not directly: it will arise in the struggles of the dispossessed who seek to reinvent the city more after their heart’s desires.

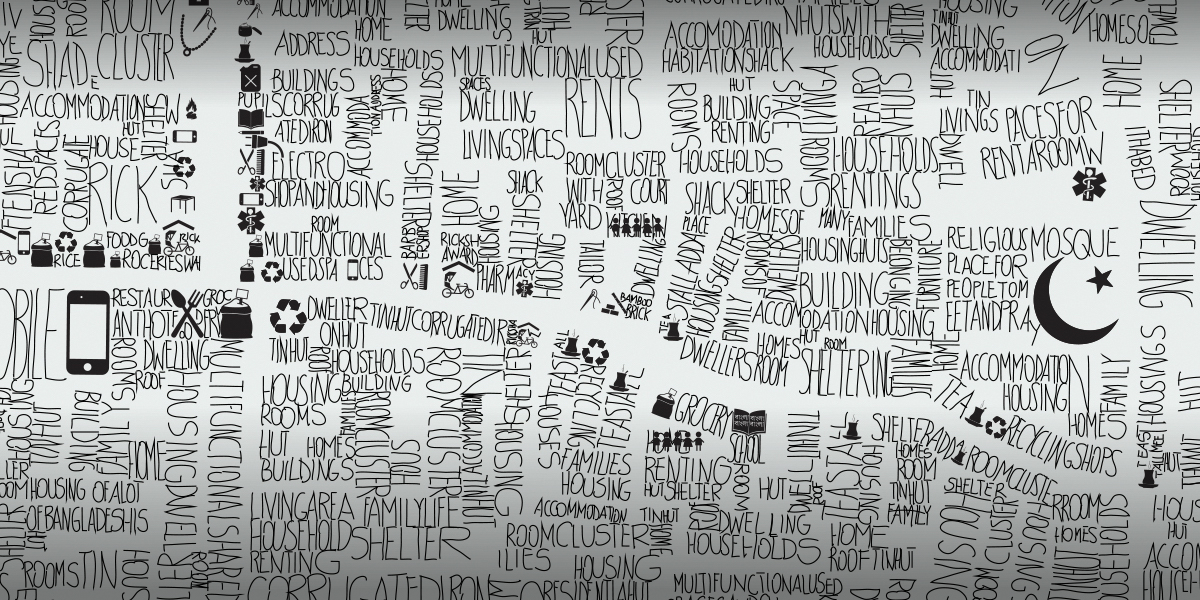

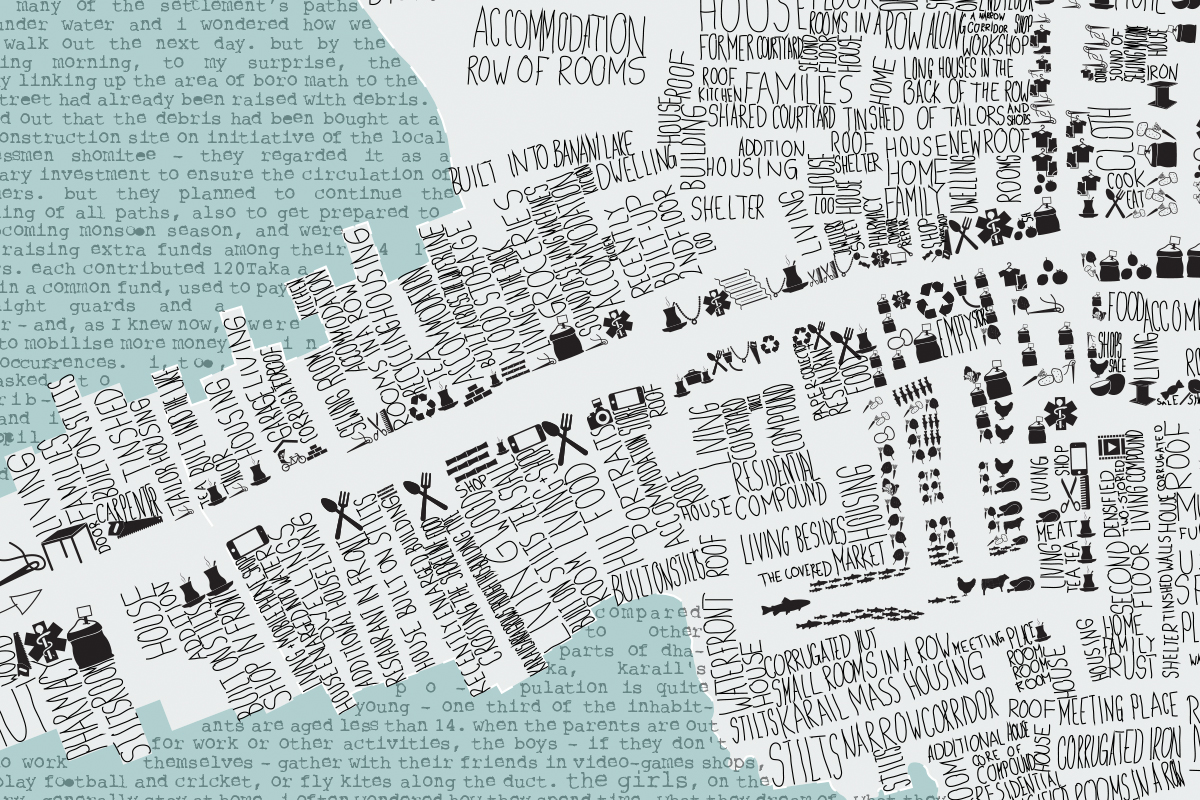

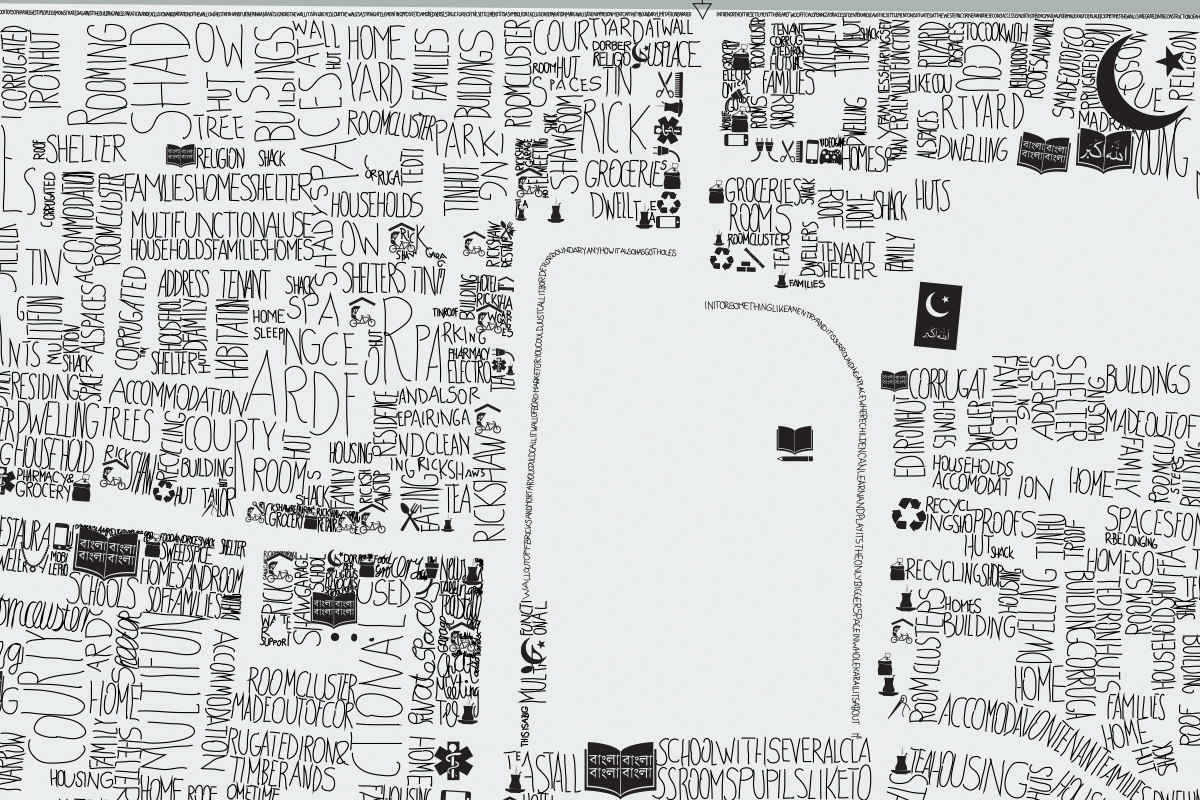

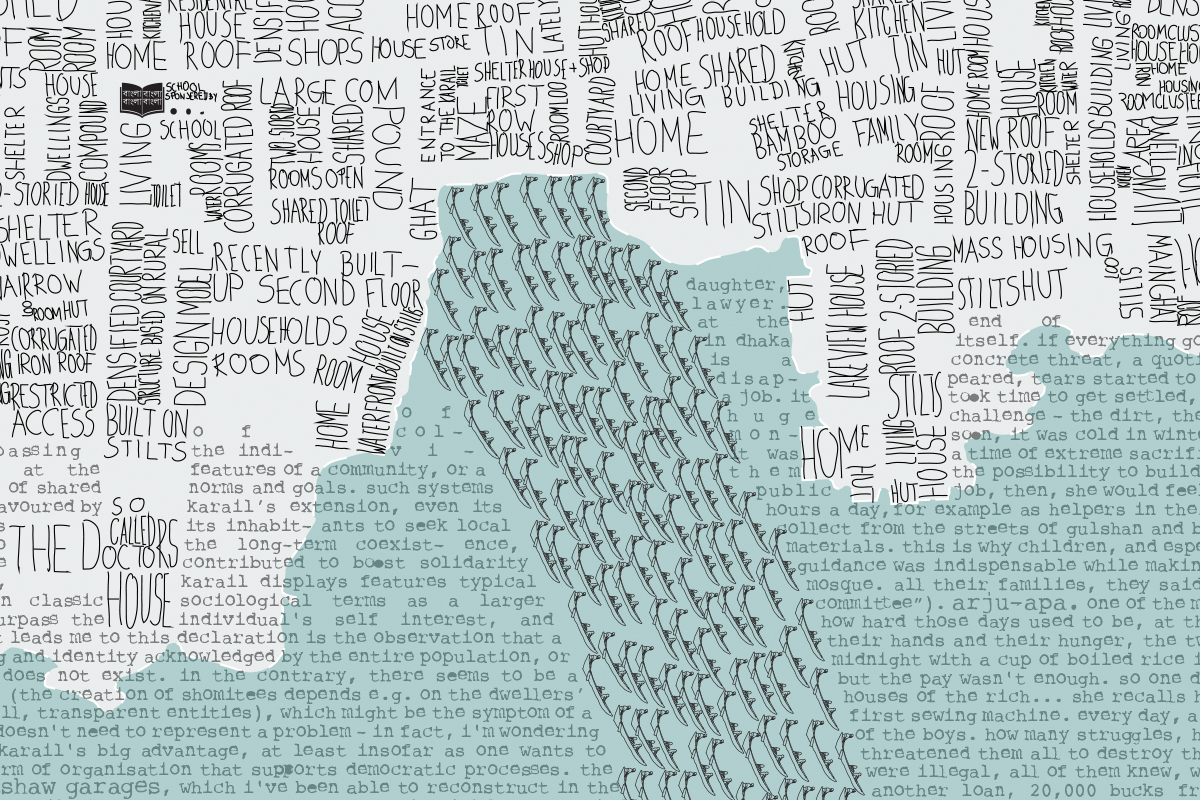

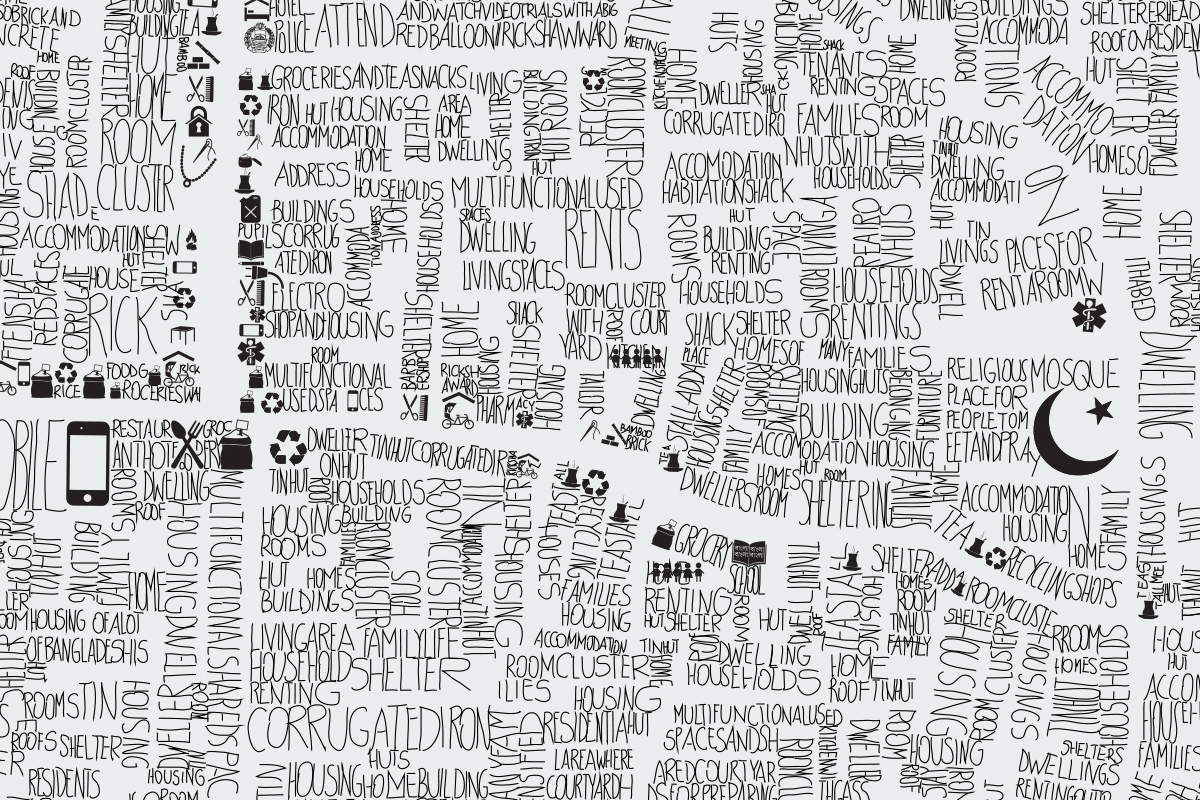

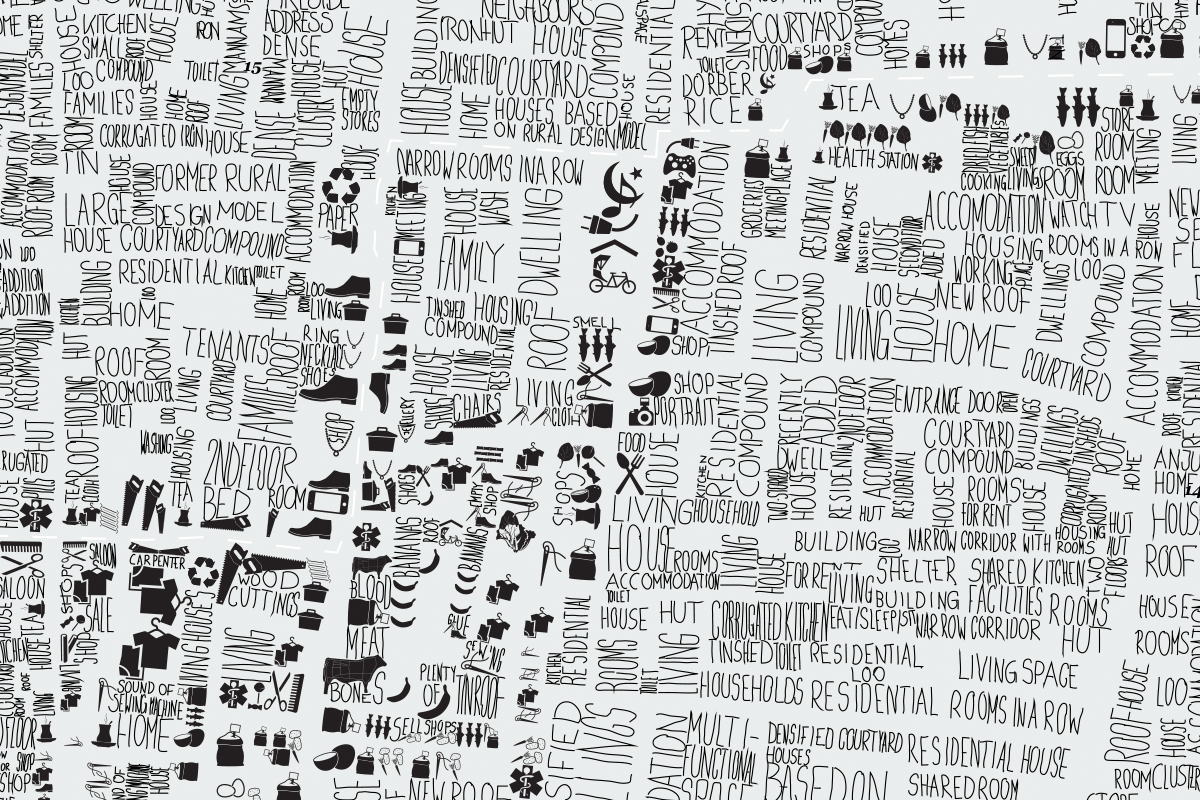

One example of a contemporary, comprehensive vision for the future of cities — a ‘New Habitat Agenda’ in its own right — comes from Habitat Forum Berlin, the NGO that convened the international 1987 Habitat Forum meeting in Berlin. Their Manifesto of the 21st Century’s Own Settlement Form was exhibited at the German pavilion in the Habitat III exhibition together with their project Information Overload. In the manifesto, Habitat Forum Berlin declares, ‘The urban heritage of the 21st century will consist of the world’s self-organised settlements’. The manifesto opposes the myth of informality and the generalising category of ‘slum’ when referring to the world’s self-organised settlements (SOS). According to Habitat Forum Berlin, SOS are not to be seen as the manifestation of ‘missing development’ in the Global South but rather as a planetary phenomenon, a result of neoliberal policies.

They write that ‘self-organised settlements, the neoliberal age’s most inherent settlement form, are currently also its most hopeful’. They demand that SOS be granted their own place in the history of human settlement and as such treated as cultural heritage. This inherent shift of perspective — not looking from outside the SOS seeking to ‘upgrade’ or brutally erase it through planning, but rather looking from within it as a dweller demanding to be seen — is a step toward recognising SOS-dwellers as human beings eligible for the right to housing. The perspective from the ground, where everyday life contradicts the promises of neoliberalism, is being shared by more and more people worldwide. Left behind by formal planning systems, their basic act of ‘habitare’ becomes a political operation.

At this year’s Habitat conference, the possibility of a future beyond capitalism — or any alternative to business as usual — was dismissed. While political struggles became part of the official debates in Vancouver via Habitat Forum, the absence of an integrated platform for dissent in Quito demanded that alternative debates be organised autonomously off-site. Concluding his honorary lecture at the Central University of Ecuador on October 20, David Harvey asserted, ‘we have to rethink the dynamics of capital in the contemporary era and recognise how to talk about urban futures without talking about the future of capitalism’, which he bet was not being discussed at Habitat III. Without questioning and transforming the systemic causes of poverty, whether urban or rural, it is impossible to eradicate it, as the UN has set out to do. Writing agenda after agenda in hollow managementese will not bring UN–Habitat or the international community any closer to international solidarity in human habitat production. As cities continue to grow in population without democratic control of the surplus, so will their marginalised inhabitants’ discontent.