A cargo vessel bearing the Cambodian flag, the Jie Shun, floats inactive in the El-Adabiya port south-west of the Suez Canal. On the 28th of August 2016, Washington calculates its coordinates and informs Cairo of the tarp-shrouded bulk freighter’s location. Upon arrival a year later on the 1st of October 2017, Egyptian customs agents inspect the vessel and discover roughly 30,000 soviet-style rocket propelled grenades concealed beneath containers of iron ore. The Jie Shun sailed not from Cambodia, but from North Korea. This discrete maneuver illustrates the type of rogue tactics the DPRK uses to ensure meager economic survival amidst, thus far, eight rounds of unanimously imposed U.N. sanctions since the nation’s first nuclear test in 2006. Since then, sanctions have expanded to include the trade of arms and military equipment, iron, seafood, mineral, coal, luxury goods, caps on oil imports and North Korean labor exports, along with asset freezes for those involved in the DPRK’s nuclear program.

Just weeks prior to Jie Shun’s arrival in the Suez Canal, an executive order by President Trump enabled the Treasury to block any entity engaging in transactions with North Korea from the U.S. financial system. The order attempts to target those who “enable this regime’s economic activity wherever they are located.” Furthermore, United States Security Council Resolution 2375, adopted on 11 September 2017, now restricts textile exports, an industry formerly untouched. Manufacturing is the largest industry in Pyongyang, and the third largest in the entire country. Resolution 2375 aspires further to “starve the regime of any revenues generated” through joint ventures to “stop all future foreign investments in technology transfers to North Korea’s nascent and weak commercial industries.”

In such an aggressively sanctioned economy — the effects of which make life more unbearable for the North Korean population rather than halting their government’s nuclear programs — the U.S. State Department Bureau of Consular Affairs urges tourists to “consider what they might be supporting.” The Bureau even speculates that tourist revenue may be channeled to fund nuclear development. This, with the Treasury block, would seem to suggest that by engaging the DPRK’S small accommodation and service industries, a tourist’s monetary trail could constitute a series of “enabling” transactions between the individual and the state. Their movement, access, and expenditure are thus politically bound to risk.

Western tourism to North Korea allegedly ranges from four to five thousand visitors annually; and while the U.S. State Department does not record the number of Americans who visit, Koryo Tours, a, Beijing-based travel agency offering trips to the DPRK, estimates that an average 20% of its clients travel from the U.S. (when political tensions have eased enough to permit American passports). Founded in 1993 — the same year the International Atomic Energy Agency accused North Korea of violating the Non-proliferation Treaty — Koryo Tours, with their claims of providing “Access,” “Experience,” “Innovation,” “Knowledge,” “Commitment,” and “Projects,” promises to “allow you to go further and see more than you ever imagined” in “one of the least understood” countries.

Itineraries are planned in advance to correspond with national holidays and events, like weekend trips from Beijing to participate in the Pyongyang Marathon, Kim Il Sung’s birthday, or an eleven-day “Unseen Korea” tour. Coordinating visits to Russia, Turkmenistan, Mongolia, and Tajikistan as well, Koryo Tours unifies a small constellation of former Soviet blocs and satellite states under the auspices of a now-familiar ideology of responsibly-facilitated tourism, a product of globalization formed in the context of the “steadily expanding international order inaugurated by the end of the cold war,” as articulated in a letter Barack Obama left for then-incoming president-elect Donald Trump.

When traveling to Pyongyang, one chooses between the Yanggakdo, Koryo, Sosan, Pothonggang, Haebangsan, Pyongyang, Ryanggang, and Youth Hotel, the eight hotels currently hosting foreigners. Of them, Yanggakdo Hotel absorbs the vast majority of Pyongyang’s tourist economy. An “average” TripAdvisor review remarks a “dated but comfortable” interior, that strikes visitors as “poor by global standards,” and overall stylistically reminiscent of a “Soviet era liquidation sale.” Summarily stated by one reviewer: “A Step Back in History…very special…it is very much in the Soviet style.” A review titled “A Hilton Stuck in the 80s” comments similarly: “I stayed 4 days in the hotel while taking a tour in the DPRK. Honestly, I was expecting something worse, but this hotel is not bad at all. It isn’t a 5 star though.”

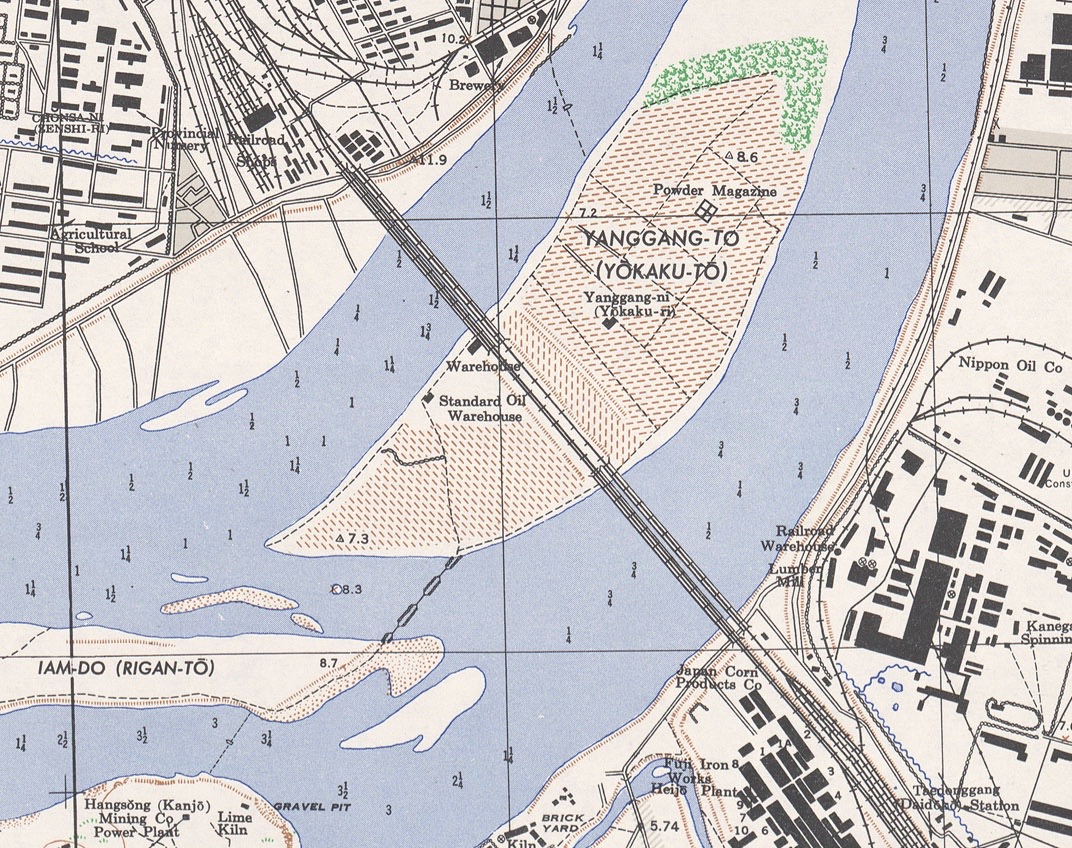

Located on the eastern edge of the Yanggak island along the Taedong River, Yanggakdo’s landscape doubly assures that tourists neither wander beyond the property limits nor leave the island unless accompanied by appointed tour guides at specific times of the day. These are restrictions many guests note as having known prior to booking. “Anyone visiting North Korea will already be informed about the reality of the place. Tourists don’t accidentally show up there,” soberly reads one review. “Not sure if we were allowed to stay anywhere else anyway, but it was a really great hotel! . . . lots of video cameras and 70s decor! . . . Just following on from what others have said—by North Korean standards this hotel is fine.”

Many comments across the spectrum of TripAdvisor’s ratings — the site’s metrics deduce 10% “excellent,” 44% “very good,” 42% “average,” 3% “poor,” and 1% “terrible”— focus positively on the revolving restaurant offering panoramic views of the greater Pyongyang urban area. Others praised features include a spa, a sauna and pool, gift shops, bars, a bowling alley in the basement, billiards, a karaoke lounge, and a casino accessible exclusively to foreign travelers. That Al-Jazeera and BBC networks are available on the in-room TVs delights, even shocks, many; that the notoriously “secret” fifth floor is inaccessible by elevators flirts with a sense of dystopic allure.

In an essay titled “DPRK” in her 2005 book Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and its Political Masquerades, Keller Easterling theorizes “spatial products of tourism” as enterprises “designed to freely conquer territory that is unencumbered by the inconveniences of politics.” Examining the Mount Kumgang Resort tourist region and the I Love Cruise as collaborative case studies along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea, Easterling describes the special economic zones brought into focus by tourism to “the world’s last remaining Cold War sites” as attractions compatible with “both communism and capitalism — fairy tales in which tourism and landscape are active solvents.”

Marooned at forty-seven stories along the Taedong shores, Yanggakdo’s experience seems, then, to lie it in its isolated verticality. It gives the impression of having “everything under one roof,” effectively operating as a “cash cow for the state.” However, commodified taste comes at a price and is confined to a cyclical crisis of equal parts itinerant boredom and errant curiosity. In Yanggakdo, Easterling’s active touristic solvent is realized as a monetized experience for guests. The money circulating within comes from without; an ironic display of excess-in-wait for the “frugal traveler in search of an adventure.” It is, after all, “the tour hotel for international visitors.” As Easterling’s formula further suggests, tourists’ views of Pyongyang’s landscape from the revolving restaurant are views many North Koreans themselves aren’t afforded — “As a western tourist you always get the best rooms!” Pursuing service economy standards of a frictionless experience, Yanggakdo augments a guest’s acquired privacy to both literal and figurative heights.

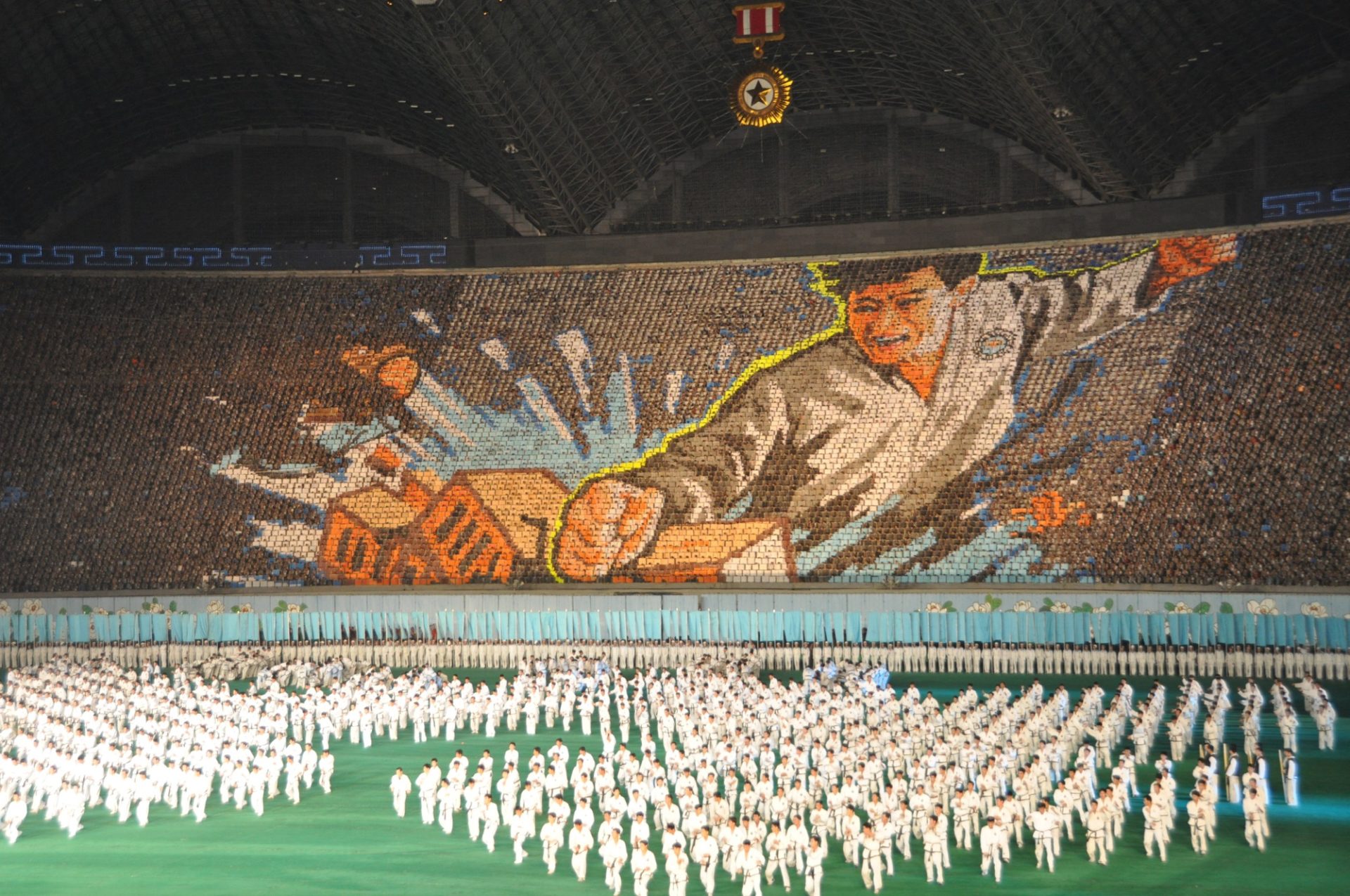

There is in fact a ninth hotel, which is comparable to Yanggakdo in its architectural expression of the DPRK’s precarious economic conditions. The Ryugyong Hotel, however, offers a less transparent window into the Regime’s ability to operate under exhaustive sanctions. Construction on this 105-story pyramid—etymologically rooted in a historical name for Pyongyang, capital of willows, and originally estimated to attract $230 million in foreign investments—began in 1987 as the DPRK undertook massive infrastructural projects to host the 1989 World Festival of Youth and Students, the largest international gathering slated to take place in the country. Logistical hyperbole in turn characterized Pyongyang’s preparation: Ryugyong was to be the world’s tallest hotel, built with intentions to subordinate to second place Swissôtel’s The Stamford (called the Westin Stamford at the time and completed in 1986) in Singapore. At the same time, the Rungrado 1st of May Stadium was constructed, which immediately became, and remains, the world’s largest sports stadium, with a 150,000 seating capacity.

Considering that Moscow hosted the previous festival in 1985, Pyongyang’s forthcoming symbiosis of political and infrastructural consolidation as the thirteenth host to a prospective 22,000 attendees from 170 countries doubled as a timely communiqué to the world vis-à-vis the 1988 summer Olympic games in Seoul, South Korea. “For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship” read the ’89 gathering’s motto, variations on the same anti-bellicose vocabulary used for festivals held in Havana, East Berlin, Sofia, Prague, Budapest, Pretoria, Algiers, Helsinki, and Vienna.

In 1992, construction on Ryugyong paused due to an economic crisis compounded in part by the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, paving way for the North Korean famine, and ossifying a grim turn of the century decade for the country. It stands abandoned to this day as the world’s twenty-eighth-tallest building. To suggest that its quarter-of-a-century presence in the rapidly expanding Pyongyang skyline merits the international mockery it has received—fatalistically nicknamed the “hotel of doom” by Western journalists, labeled an architectural sin, and deemed the biggest mystery in Pyongyang—would consign Ryugyong to the realm of compulsive political affect ranging from imaginative resentment to the very policies governing U.S.-North Korean relations since American involvement in the Korean War.

Egyptian global engineering and construction contractor Orascom invested in Ryugyong in 2008 in exchange for a 75% stake in Koryolink, North Korea’s first and only 3G network. By 2011, the reflective glass exterior was completed. Following the political dimensions of touristic fantasies, an Esquire article published the same year opines about a sanctified belligerence towards the hotel: “the worst building in the history of mankind…even by communist standards, the 3,000-room hotel is hideously ugly…like some twisted North Korean version of Cinderella’s castle.” Such desperate descriptions act as a palliative for a deficit of knowledge about North Korea, a process dialectically in lockstep with glorified American inter- and post-war mobilization. Economic production based on planned urban obsolescence, disinvestment, and privatization, for example, “underwrote Cold War American practices and values from economics to geopolitics.” Pyongyang’s postwar Juche ideology, on the other hand, intended to distinguish itself from Soviet Union Marxist-Leninism, and equally important, abolish Japan’s asymmetrical colonial occupation by taking control of industrial development, iron works, mines, and fisheries.

In 1953, a post-war master plan for an internationally standardized city, including the expansion of facilities for foreign visitors, was designed in the wake of the U.S.’s destruction of the northern peninsula. A devastated Pyongyang had an opportunity to programmatically redesign the city in a way that most other socialist cities did not experience. This approach was heralded as a model for other cities in terms of symbolic and spatial design. During the first three-year construction plan (1954-56), Pyongyang received assistance from both Bulgaria and Hungary. To this end, the ’60s through ’70s marked epochs of relative stability and growth for the DPRK’s capital. High-rise housing developments appeared along major boulevards with a mixed typology of high to mid-rise buildings. In microdistricts inspired by Moscow’s 1935 plan, green zones were spatially balanced with residential, urban, and industrial zones, referencing Ebenezer Howard’s garden city designs. Monuments to a developing political project were erected, and major public squares nodally connected parts of the city. At 170 meters tall, the Juche Tower, constructed in 1982, stands just one meter taller than the Washington Monument; Kim Il Sung’s statue, a mere 22.5 meters, 116.5 meter shorter than the Statue of Liberty. Ryugyong, 330 meters, stands in a residential square just north of the city’s center surrounded by the Potong River.

After Orascom’s intervention, Kempinski headed Ryugyong’s project management. As the self-described “oldest European luxury hotel group” whose “prestigious heritage” forecasts a “bright future” for clients in Croatia, Austria, Myanmar, Jordan, UAE, China, Qatar, Oman, Cuba, Ghana, and Egypt, Kempinski’s mission to “satisfy the expectations of the stylish and discerning traveler” by “bringing a story to life” also came to a halt in 2013 amidst rhetoric of a thermonuclear war issued against South Korea from the North.

Ryugyong captures one’s gaze, as it was ostensibly intended to, whether from Yanggakdo’s revolving restaurant or on Google images; whether from Pyongyang proper or halfway around the planet. Its production was a response to an unprecedented occasion; its ongoing stasis as a stock image is an unintended consequence of a restructured global order. “The mutual attraction between tourism and the DPRK exposes political dispositions in both worlds… the capitalist must also choose opportune moments to declare the DPRK evil and itself pure,” continues Easterling. Rygugyong’s exorbitant vacancy is no exception to this seduction.

America’s belligerent stance toward North Korea, characterizing it as part of an ‘axis of evil,’ galvanizes the DPRK’s most violent military programs, and places the two countries back in Cold War architecture of symmetrical mimicry, fragility, and innocence. This, together with the neoliberal belief in a slow inculcation of capital’s superior logics, constitutes a military-market containment of sorts.

As a skyscraper, it aspires to the standardized global model of development “more familiar to the world than the context of its host country.” As an unfinished project, it bewilders the fragile and finite capitalist life cycle of advantageous investment opportunities; and as the glass exterior reflects gazes from near and far, it innocently defies the American logic of sanctions and imperial dominance as the inevitable consequences of time-tested coercive policies. Stubbornness is perhaps a more realistic expression for Ryugyong, which, like U.S.–North Korean relations, exemplifies nuclear deterrence—a long-term balancing act suspending its target audiences in short-term disbelief. And for the Yanggakdo, “be thankful for the views from the room over the river towards the pyramid-shaped hotel…it’s supposed to open soon, but I hear it’s tilting.” The hubris of unrestricted height serves the speculative imagination on both sides of the enduring iron curtain, after all.