In the modernist living room

My mother has a penchant for modernist furniture. Our living room is a carefully choreographed landscape of Eames Lounge Chairs, Le Corbusier’s LC2 armchairs, low crystal coffee tables, a couple of small marble Eero Saarinen Tulip tables. Altogether a rather generic and cold interior, a posh Gesamkunstwerk complete with a treadmill and a bench for abdominals, scattered African artefacts, a white cat. And of course a fireplace, needless to say, a modernist angular fireplace in black marble and tek wood. Despite its funereal look, sitting in front of it is one of the finest wintery delights. Around a month ago, after a Sunday lunch, my grandmother sat on the LC2 armchair in front of the fireplace and got stuck in it. This seemingly domestic-corporeal incident struck me to the point that I decided to write a critical analysis of a drawing, part of the Canadian Centre of Architecture’s collection, representing the Modulor Man by Le Corbusier.

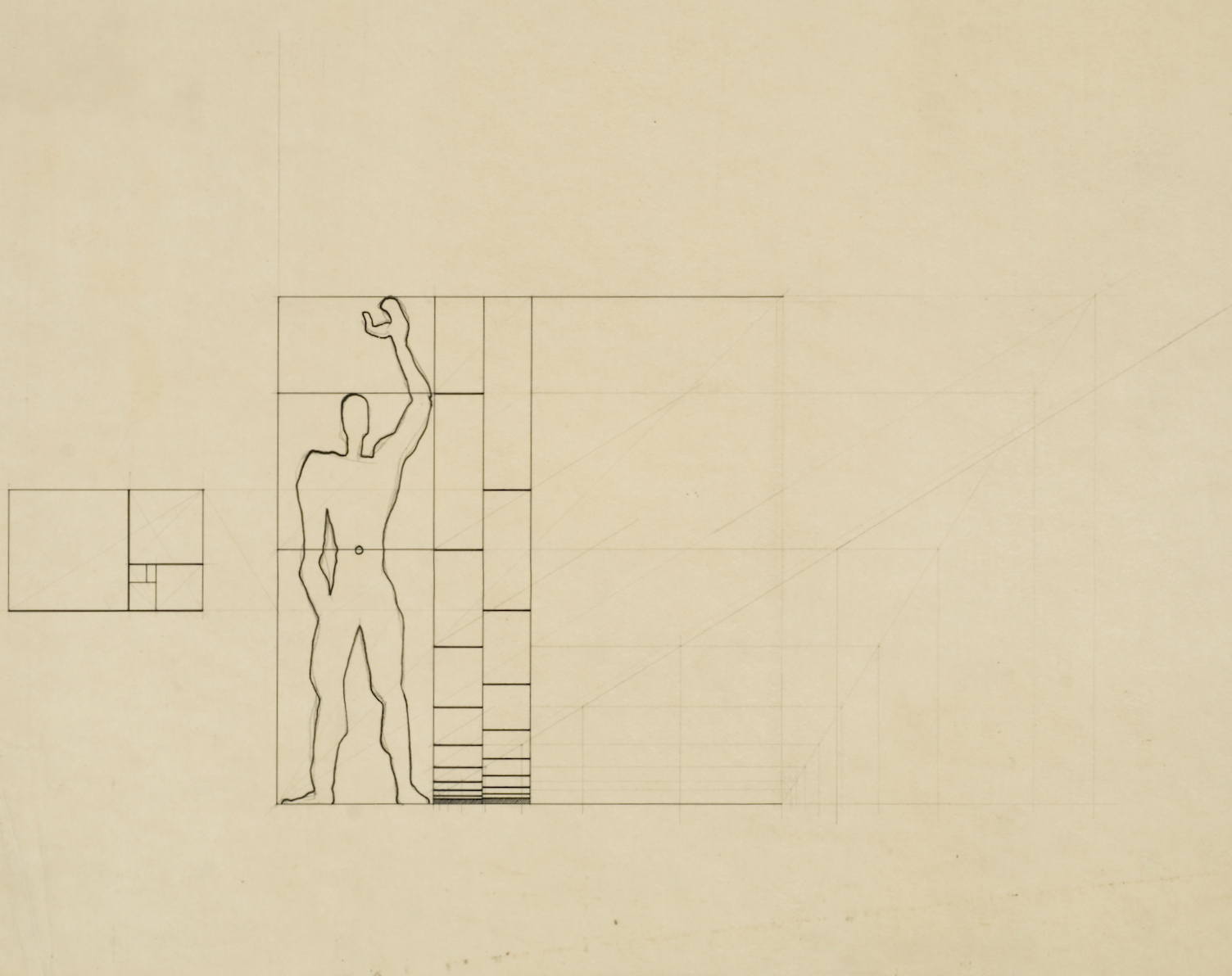

The Modulor Man and other dummies

The Modulor is an anthropometric scale of proportions created by Le Corbusier in 1948 to embody a “range of harmonious measurements to suit the human scale, universally applicable to architecture and to mechanical things”. Situated within a certain Western humanistic programme that goes back to Protagora’s ‘Man, measure of all things’ then revived by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, Le Corbusier’s Modulor is an updated version of this masculinist and ableist universalism. The Modulor Man is a healthy white male enhanced by mathematical proportional gimmicks ‘of nature’, such as golden ratio and Fibonacci series. He represents the normative and normalised body around which Le Corbusier conceived his designs. As a result, most modern architectural forms are all tellingly calibrated on a similar standard, the healthy white male body. Considering this fact, it is easy to understand why the LC2 armchair turns into a trap for the plump body of an eighty-six years old lady with limited mobility.

Humanist Humans and Other Humans

The ideal normative body of the Modulor Man has more to do with the schemes of dominationof a given society, than with an objective statistic of physical average. To various degrees, this norm is harmful for all the bodies: although favouring some over others, it generally introduces a restricted notion of what accounts as human. It is not merely a canon of perfect proportions, but a normative statement, and such a long standing one that it ended up being regarded as ‘human nature’. Humanistic universalism introduced a binary between Sameness and Otherness, in which the notion of difference from the norm equals pejoration. In the words of disability studies pioneer Rosemarie Garland Thomson, the aberrant body “framed and choreographed bodily differences that we now call ‘race,’ ‘ethnicity,’ and ‘disability’ in a ritual that enacted the social process of making cultural otherness from the raw materials of human physical variation.” In so far as being different from the norm spells inferiority, a system of compulsory human values is set: able-bodiedness, whiteness and maleness. This standard of Sameness excludes and discriminates the pathologised, racialised, and sexualised Others.

The silent treatment

Since the Renaissance, the ideal of bodily perfection doubled up as a set of architectural values: Vitruvian Man built around this notion of idealised proportions for both the body and architecture. Modernist architecture went even further, it ceased to account for an ideal body and became accountable for attempting to normalise real bodies. Man was not the measure of all things anymore: the human body did not shape design, it was design that aimed at shaping and correcting the human body. The standard of physical and mental perfection became integral to modernism’s eugenic project and the relationship between body and architecture turned into an orthopaedic one, in an attempt to standardise human beings through medical correction. The Modulor Man was not only the ideal human model for ergonomics, but also the final result of a process of human betterment triggered by modern architecture itself. While responsible for a violence that affects the body with an intensity proportional to its corporeal difference from the norm, architecture proved to be incapable of providing positive solutions for the ‘aberrant’ body. The cluster of modernist furniture in my living room is definitely not going to turn my grandmother’s body in one that is younger, healthier and more slender.

Nietzsche in the modernist living room

Having witnessed the crisis of the validity of the European humanistic model, Friedrich Nietzsche claimed the end of the ideal status attributed to the human. I imagine him as a bewildered guest in the modernist living room, surrounded by orthopaedic furniture and an elderly lady trapped in the LC2 armchair. In all likelihood he would have uttered: “Where you see ideal things, I see — human, alas! All too human things”. There is both a sense of relief and a bitter aftertaste to the claim that projects of moral and physical sublimity are unlikely to succeed when it comes to the real human material. Getting to know the rather absurd origin of the Modulor human shape makes it easier to accept it: Marcel Py, Le Corbusier’s young draughtsman suggested that the Modulor Man was 1,83 m tall because in American detective stories the handsome main characters were generally this height, which also happened to coincide with six feet, a point allowing correspondence between the metric and Imperial systems. There is clearly no need to conform to this ideal standard and no fault in being unable to do so. But despite Nietzsche’s judgment and the attacks of post-structuralist forces, the Modulor continues to uphold universal standards and to exercise a fatal attraction.

Given the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s groundbreaking research regarding medicalisation in architecture and its extensive Le Corbusier collection, I think it is time to address the role of norm and standard in Le Corbusier’s work and its legacy. The radical critiques of humanistic posture from disability and feminist theory that I collected in this critical essay are not merely negative, but they propose alternative ways to look at the human from a more inclusive and diverse angle.