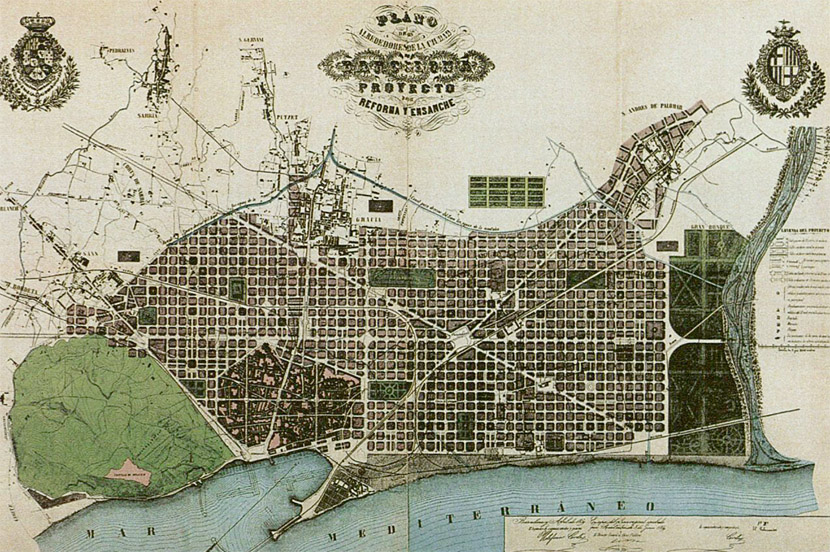

Surrounding the borders of Barcelona’s old city, the Eixample district is an unmistakable grid of some 900 seemingly similar city blocks master planned by Ildefons Cerda. Characterized by its unique 45 degree cut corners and home to Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, Casa Mila and Casa Batlló, the area stretches from Mies Van der Rohe’s reconstructed Barcelona Pavilion at the base of Montjuic to Jean Nouvel’s Torre Agbar at Placa Glories Catalanes. From above, the density and magnitude of the city-block morphology is an unimaginable exercise in master planning and replication. From within, the uniqueness of each city block is a disorienting yet atmospheric pedestrian experience. The area however, did not develop as Cerda had originally planned. What began as a utopian master plan championing publicly accessible green space has today become an enclosed and privatized neighborhood specifically lacking this publicly accessible green space. While recent efforts have been made to revitalize the neighborhood more in line with Cerda’s initial intentions, the entire implementation of Cerda’s vision is these days wholly impracticable.

The Eixample master plan was devised as a necessary extension to Barcelona’s medieval city walls during the second half of the 19th century. As the Industrial Revolution’s influence began to rise within Spain, newly constructed factories and the subsequent increasing labor demands drew rural citizens to the urban centres of both Madrid and Barcelona like never before. Due to poor living conditions, overcrowding, a rising cholera epidemic and a population density as high as 1500 inhabitants per hectare, the Madrid government authorized in 1854 the destruction of Barcelona’s medieval walls and called for a competition for the design of a new expansion of the city. Ildefons Cerda (December 23, 1815 – August 21, 1876) was an urban planner originally trained as a civil engineer who left his job in the civil engineering service to begin working on a grid based plan that would come to be known as the Eixample. At this time, grid or radial based urban planning principles were being implemented or experimented with in New York, Buenos Aires, Paris and London. Unable to find relevant planning precedents for his unique vision however, Cerda undertook the task of writing his own from scratch.

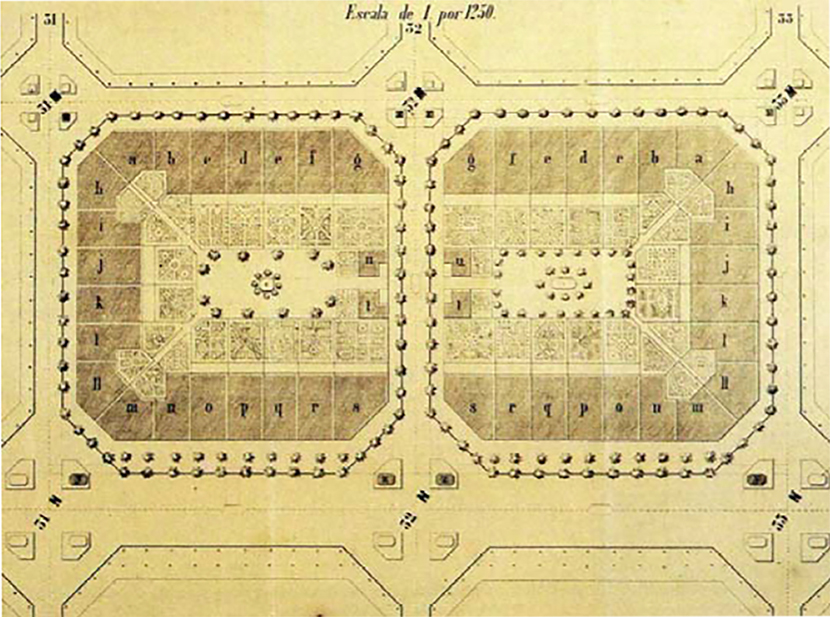

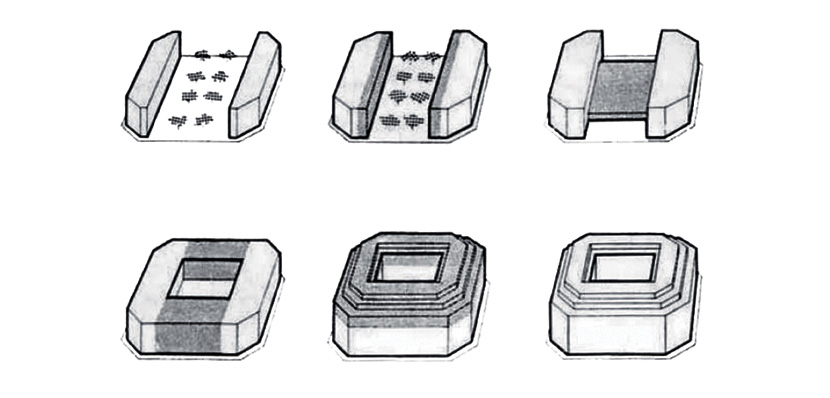

At the core of Cerda’s master plan was the creation of the manzana – a city block structure that had been meticulously studied and detailed. Originally, each manzana was to be built up on only 2 or 3 sides, with a depth of 20 metres and a height of 16 metres. The length of each side would measure 113.3 metres with a precise area of 12,370m2. In between the 2 or 3 built-up sides a recreational green space would allow for a maximum amount of sunlight and ventilation to penetrate every unit in the manzana while simultaneously providing a green belt for the entire city in all cardinal directions. Unique to Cerda’s manzana was the 45 degree chamfer of each corner of the city block. Cerda believed that the steam tram would come to dominate the future of transport in Barcelona, and as such the 45 degree chamfer was designed to accommodate for the tram’s turning radius.

By 1855 Cerda had surveyed and drawn up Barcelona’s first accurate topographical plans for the preliminary expansion project which was soon approved by the city council. In 1859, however, a newly elected council held an urgent projects competition for the expansion area citing that Cerda’s original plan took no consideration of the existing medieval city. Cerda’s plan was again successful in the competition (albeit with slight modifications), but for unknown reasons (although one can speculate about political partisanship or poor personal relationships) the city council repealed the competition and declared it void. It subsequently selected Antonio Rovira y Trias and his radial centric design as the winning master plan. However, the Madrid government remained interested in Cerda’s plans and allowed him to continue working, albeit at his own expense. In 1860, and with Madrid’s approval, Rovira y Trias’s plan was scrapped and Cerda’s plan again passed, although with major compromises.

At an urban scale Cerda’s plan divided up the Eixample into different districts, zones and sectors with North-South and East-West running, regularly spaced streets. The streets would be built to a width of 20 metres with 5 meters dedicated on each side for pedestrians (with the exception of Gran Via which was to be 50 metres wide and Passeig de Gracia which was to be 60 metres wide), while a district would be defined as a 20-block self-sustaining unit with direct access to shops, services, markets and schools. Larger institutions such as hospitals, cemeteries, parks, plazas and industrial buildings would be spaced at calculated, even distances within each zone providing an overall utilitarian radius of access for Eixample inhabitants. Implicit to Cerda’s plan was a network oriented approach to city design where the street layout and grid plan was optimized to accommodate the mobility of not just the pedestrian, horse drawn carriage and stream tram, but infrastructural works such as gas supply lines, large capacity rain sewers and effective waste disposal lines. Revolutionary for the time, Cerda’s utilitarian and efficient urban plan sought a comprehensive enhancement of mobility which went beyond mere transportation planning principals to include a more holistic view of planning for the movement of goods, information and energy.

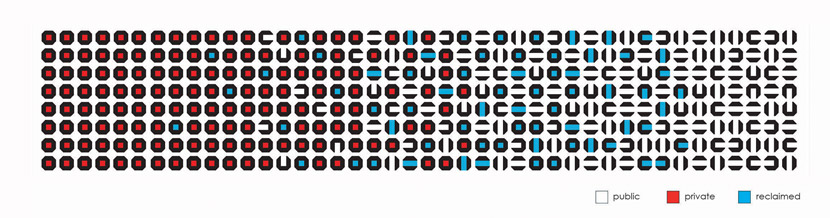

While only 1 of the 2 originally planned diagonal streets was realized, of greater consequence in the implementation of Cerda’s plan was the transformation of the meticulously studied manzana block. Cerda’s theoretically planned, two or three sided, 20 metre high manzana lacked profitability and with no strict government controls in place, the majority of the blocks were soon built up on all four sides while far exceeding their originally planned height. Likewise, manzana blocks which were planned as public facilities (such as schools, markets and social centres) were instead developed without regard to the plan: private leasable space. Later, under Franco’s regime, the manzana blocks were further built up, resembling something more akin to Soviet block-brutalism than a greened, ventilated, publicly accessible neighborhood. In complete contrast to Cerda’s original vision, the central courtyards were often closed off and are now commonly used as a car park.

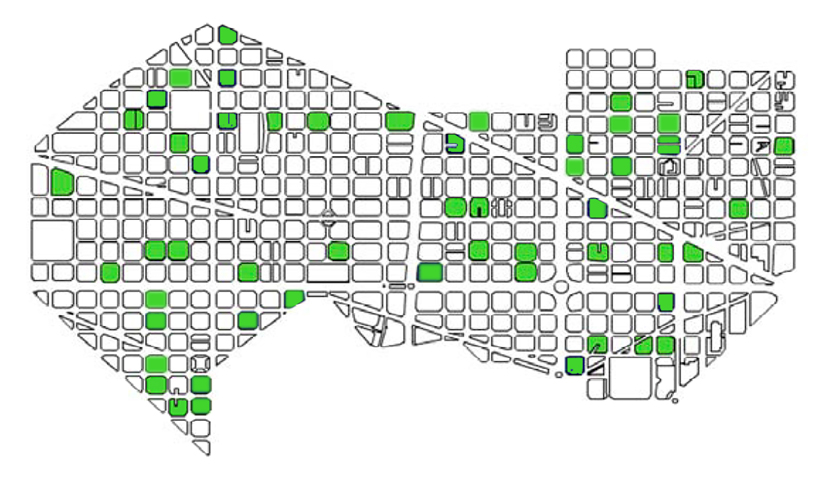

In the early 2000s in a joint venture between the city of Barcelona and various Catalan banks, the “Pro Eixample” foundation was formed in an attempt to reinstate some of Cerda’s original intentions. Pro Eixample’s main directive was the recovery and conversion of the enclosed inner courtyard of the manzana into a publicly accessible, usable green space. In total, Pro Eixample attempted to recover 50 block interiors representing roughly 100,000m2 of space. In tune with Cerda’s original intentions, Pro Eixample sought to transform Eixample so that 1 in every 9 manzanas would have a public courtyard and that all residents of the Eixample would have a publicly accessible green space within a 200m radius of their home.

A visit to the manzana courtyards provides an offbeat tourist or local itinerary to a little-seen side of Barcelona. Unfortunately, many of the reclaimed courtyards lack a standout landscape or architectural design impetus that would position them as a tourist destination. However, even if the courtyard reclamations are meant to be small-scale, local interventions for the enjoyment of the nearby manzana residents rather than the broader public, many of the conversions seem to do very little in terms of providing actual shaded green areas. Instead, many reclaimed courtyards appear as normative, dusty, hardscaped open plazas with few users.

A few of the courtyard conversions however, are indeed exceptional. At the Jardi de la Torre de les Aigües an immense brick water tower anchors an ‘urban beach’ and wading pool. While the tower is no longer functional, the historic and unique form in addition to the courtyard conversion made it a popular and well-used space.

At the Jardines de Montserrat Roig, a copper beer kettle-leftover from the Damm brewery which previously occupied the site remains as an interactive playscape. At the same time, fans of Enric Miralles can lounge on one of his sculptures at the Jardines Jaume Perich.

A Public space furniture at Jardins de Jaume Perich.

Mutari

Pro Eixample has published the book ‘Els Interiors D’illa de L’Eixample els Significats dels Seus Noms’, detailing many of the interior courtyards with explanations of their names. It is not accidental that many of the gardens are named after women as the Barcelona street nomenclature is exclusively male. It is difficult to imagine what the Eixample neighborhood would have looked like today had Cerda’s plan been rigorously implemented. The neighborhood as it stands, is functional, atmospheric and charming. It has by and large succeeded as a dense, working-middle-class area of Barcelona. In these terms it is difficult to critique, especially in comparison to other cities that have forsaken their historical plans for a gentrified and ubiquitous banality of shopping mall, big-box pretension. It rather comes down to the question of ‘what if?’. Had Cerda’s plan been realized, Eixample could have developed as the singular most green-belted and publicly oriented area of its time and would have been far ahead of present-day urban renewal efforts. Ildefons Cerda finalized the development of his Eixample plan at his own expense. Although in general terms his plan was realized, he died penniless, credited with a neighborhood that is a distant reflection of his initial intentions.

For further information and locations of the reclaimed courtyards in Barcelona, this pdf-file provides a complete listing.