One of the more noteworthy concepts that the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016 communicates was a simple one: prioritise locally added value over value extraction. Of course, you might say, that’s common sense. Or is it?

It’s not a new argument to say that cities are increasingly morphing from social configurations to investment vehicles. Today, urban spaces and amenities are only realised, and can only survive, if they have a viable business model that produces a healthy profit. Such so-called ‘progress’ relies all too much on debt and fossil fuel, it eats away at both local value and the planet’s resources. It’s shareholder value over use value, short-term profit over sustainable evolution, private interests over public good, and generic, disconnected real estate objects over locally and socially-attuned architecture. Urbanism reduced to a game of Monopoly.

This value extraction applies to many aspects of society and urban life. Deliveroo and Uber are creating an on-demand precariat, AirBnB is making money off our homes and public transport, healthcare and other services have steadily been privatised. Perhaps the largest profit machine in cities is real estate. After both Oliver Wainwright and Jack Self’s IABR–2016 talks about real estate and housing, as well as the recent European trend of self-built homes which is also represented in the biennale, we were left wondering: do self-builds create more local value compared to ordinary real estate development? And does it offer a solution to the housing crisis?

When keeping it real goes wrong

Real estate is not in the first place about local value development. Sure, it relies on (or tries to create a) demand for space, but the main aim is not to create the largest possible use value; the guiding principle is a high profit margin. As Oliver Wainwright (the architecture and design critic for the Guardian) showed in his daunting talk at IABR–2016, a 20 or 25 per cent return on investment is normal for new developments in London. It is turning urban spaces into financial abstractions, units on the balance sheets of shareholders, the kind of people who are usually not living in or near such a development (if they are even people at all). Wainwright clarified: “no hedge fund will ever promise you such a return”. But who’s paying for their profits?

We all are. In the first place, large developers are usually favoured by local authorities through tax breaks, land price reductions and other incentives, all in place to get that much coveted area development going (since real estate development is generally believed to indicate progress). Moreover, whether it be houses or offices, for developers to make such ridiculous returns on investment end users will inevitably be sold spaces that are ill-equipped to meet their needs. That is, unless you are one of those people for whom money is no object. In all other cases, material and functional economisation will curtail use value, to ensure the high profit. And finally, another way developers milk out value is on the urban scale, on actual urbanity. Their focus is on the development of plots, not on good public space or common amenities (other than retail). If greenery is promised, we should especially be wary of what’s sold to us, Wainwright warned – something we also tried to point out earlier this year.

The public sector is not really incentivising developers to do it right. Worse still, the role of London’s planning department has, according to Wainwright, shriveled to “safeguarding the profits of developers”. Viability assessments make sure projects are profitable enough for the developer. One feature of the UK planning system is Section 106, a “mechanism which makes a development proposal acceptable in planning terms”. For example, it can demand a certain percentage of affordable housing or a sliver of “privately owned publicly accessible space” (POPS). In reality however, developers can renegotiate affordable housing demands, and, as Wainwright showed, and as we have discussed before, POPS often turn into dead spaces. Ewald Engelen, Professor of Financial Geography and respondent to Wainwright’s lecture, showed his perplexment: “a 25 per cent return on investment is a fixed ‘cost’, but the percentage of affordable housing is variable?”

The weight of social value has drastically diminished in the urban equation. As Engelen said: “we live in financialised times”. Financial value has become an increasingly dominant driver. Urban quality reduced to financial values is dangerous, because financial markets suck up real world value.

BIY: cutting out the middle man

But if developers demand such outrageously high profits from spatial production, why not simply cut them out of the equation? That’s what more and more local authorities and citizens are thinking, and doing. “Self-builds”, “Baugruppen”, and “zelfbouw” are just a few ways to define variations of building-it-yourself (BIY), whether done individually or as a collective. The end users (who are the commissioners), together with architects, decide on the design of their homes, and then take care of the construction themselves or have contractors do it. IABR–2016 also showcases several such real world projects; they provide an alternative to real estate landscapes and they show innovations in the field. Self-building could alter the function of homes as profit machines. Of course, the largest part of the built world is self-built, with no developers or (even less) architects involved. But in more and more (mostly Western European) cities, BIY has recently become a policy, an instrument and even a marketing tool for urban development. Countries like the Netherlands and Germany are frontrunners in the self-build trend. But how progressive is this development really? And how does it contribute to the housing question in general?

Last year we published Sonia Mangiapane’s visual exploration of the outcomes of this trend in the Netherlands. Our conclusion was that because of restrictions in size, volume and aesthetics, and cultural preferences, most self-builds (except for the occasional freak) are relatively uniform.

BIY is promising in terms of locally added value over value extraction. You could assume that cutting out the traditional developer is a good move. After all, end users have the largest interest in high future use value of the home, as well as its visual and functional effect on urban quality. Architects and contractors are in closer contact with the future users, so you could expect a better incentive to deliver good work. Even if some of what used to be the developers’ profits are now creamed off by the architect or the builder (whose roles are usually greater in BIY-processes) and if the home is still a personal investment to the BIY-er, this type of urban development could be less prone to speculation and value extraction.

However, it’s not all as rosy as it may seem. While it is – like fashion – a nice way to express one’s taste and social codes, BIY is not the magic potion that will cure the ills of the urban housing crisis. For one thing, because space for self-builds is terribly limited, especially in popular cities, governments who promote BIY (such as the city of Amsterdam) have paradoxically also proven to be reluctant to provide space for it. They would still rather sell a large swathe of land to one developer, cash in on it, and have the developer build up an entire neighbourhood, instead of selling individual plots to BIY-ers and having to deal with all the handling that goes with it. It exposes an internal conflict: the planners promoting BIY are often blocked by the city’s real estate department. Urban researcher Vincent Kompier says that in cities other than Amsterdam the approach is a more logical part of the planning apparatus, and “not only used as a fix for places where the crisis has frustrated business as usual.” What’s more, the plots issued for self-building are usually taken by the people who have the best connections and are well-versed in the relevant regulations.

An ad hoc encampment for people who tried to keep their spot on a waiting list in Amsterdam, when self-build plots were sold on the basis of ‘first come, first serve’. The result was that late 2014, people camped for three weeks in order to get their desired piece of land. Even a baby was born here.

But the main problem with self-builds is financial accessibility. Even if there were enough space, it wouldn’t solve the housing crisis, because BIY is a middle-class affair, it’s quite expensive and therefore it doesn’t substantially contribute to a more inclusive city. One architect from a collectively developed project featured in IABR–2016 (who didn’t want to be mentioned on Failed Architecture) told us: “we tried to also provide affordable housing.” The plan for the project was also to develop modest and thereby suitable homes for people in the collective whose incomes were below average. “But the investments needed to meet sustainability requirements for new constructions are so high that it became too expensive for them.” Apparently, if we want projects to be inclusive and sustainable, it’s difficult to achieve. That can’t be right. Inclusivity and sustainability are two of the most pressing urban challenges of our time, and based on examples like these, it seems like you can’t leave them to the market. Governments should create incentives and regulations for the market to work in a positive way, and take the lead in the development of good quality and affordable housing if the market doesn’t deliver.

Newschool oldschool development

Another reason why BIY is not for everyone is that it takes a lot of time and energy. But that doesn’t have to be the bottleneck, as assistance can be hired: we see architects turn into developers, managing a larger part of the process (land acquisition, design, permits, construction, interior, etc). Simultaneously – as supply will always meet the demands of those with money to spend – more and more developers are now applying customisation to their products. Think of it as the NIKEiD-formula for homes (the basis is there, but you can tweak one or two features according to your preferences), giving BIY-ers the feeling they get something unique that suits their highly individual taste and makes them stand out from the rest.

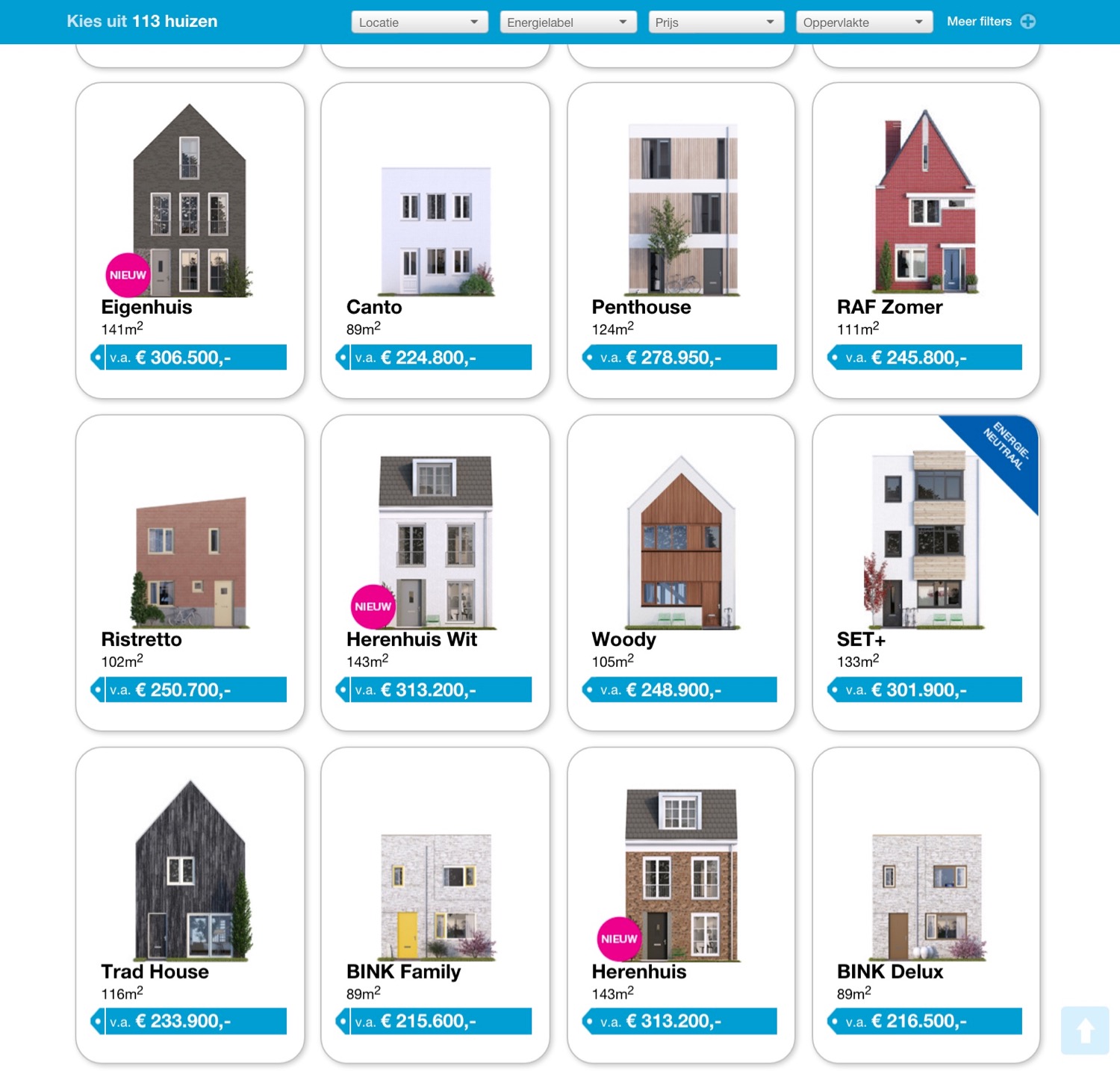

One such project, WeBuildhomes, suggests that the customer can have exactly what she or he desires: simply order your favourite future home on a website and have it up within 20 weeks. It’s not completely tailored, however: the homes are pre-designed (by actual architects, who for their creations have used names like “Ristretto”, “Birthday Cake”, “Max!”, “BINK Family”, “BINK Delux”, “Fresh” and “Fresh+”). It feels like the 21st century version of the suburban catalogue McMansion, only in mini and with a smaller demand for fossil fuels. But it’s not the desired organic, citizen-led type of urban development. A few clicks later you actually find out that the homes delivered by WeBuildhomes can only be planted in four designated locations in the Netherlands (not in cities where housing demands are highest), selected by local governments and WeBuildhomes Ontwikkeling [Development] BV. While the website resembles an Etsy-like platform connecting aspiring homeowners to architects, it is in fact just another real estate developer with a different outfit. Business as usual, not cutting out any middle man, but simply reconfiguring the dominant spatial powers.

(Sub)urban

Distinguishing “Baugruppen” and other forms of cooperative housing from individual BIY (buy a plot and plug a single family house onto it) is important. The former require a more social attitude, since cooperation is key to success. Whereas many of the new urban self-builds are suburban setups transplanted to the city, collective developing often occurs in more urban environments, as Vincent Kompier explains when he talks about examples from Germany: “it’s a matter of proportion and population. Baugruppen usually occur in, and produce, more urban scale environments. They are also less socially homogeneous than a row of self-builds. Moreover, they often have a mixed programme, offering more than just housing.” Urbanisation processes in many cities require densification, for which individual BIY plots won’t suffice. Collective development makes more sense, especially if they can indeed contribute to density and diversity. Urbanity, after all, is about variety, surprise and negotiation.

But whatever the shape, size, and ‘uniqueness’ of homes, it won’t make much difference if policies don’t change. In the end, the ‘right to the city’ turns into socioeconomic darwinism if everything is left to the market. It boils down to one question: who is allowed to live in the city and who is enabled to shape it?

Besides prioritising local value creation over value extraction, IABR–2016 also calls for an entrepreneurial state. It does so most explicitly in relation to the transition to clean energy, but we think that a determined and proactive government is also required when it comes to urban housing: both to make sure that housing market dynamics won’t result in segregation and expulsion, and to have a housing stock that is less energy-consuming, which could be a significant contribution to the decarbonisation of the world. As emeritus professor Hugo Priemus argued in response to Jack Self’s talk at IABR–2016: “the housing crisis is not a market failure; it’s a failure of policy.” Self analysed the prospects for London: “at the current rate of construction, it will take 700 years to solve the housing crisis.” That is, if we leave it all to the market and don’t come up with other, innovative and affordable, modes of living (something Self is in fact working on in various ways).

Self-builds are not going to solve the housing crisis. They just provide a customised home for those already lucky enough to get a mortgage that buys them a home (only now dressed up as they like). With the limited possibilities for BIY in popular urban areas and because it has a strong middle class bias, these micro-developments are insufficient. We need an approach that doesn’t create suburban parts of the city, but developments that are actually diverse in population and functions.

It’s time to bring back good housing policies because intelligent and inclusive plans are urgently needed. Governments should take the lead and give a more prominent role for actual architecture, so that designers can do more than dress up real estate. That way, more structural and flexible additions to the housing stock can be realised than when things are left to the market (with its more volatile supply and social exclusion mechanisms). Much of the current supply side is only driven by home-ownership and market-rate rental demands, but the need is much larger. We need suitable and affordable homes for households that are not simply composed of dual-earner couples.

Cutting the middle man is good, but a more active government is better. Good housing for everyone is fundamental, and the market can never deliver it all. Intelligent, energy-friendly and beautiful architecture can be the expression of socially diverse cities that aim to be more than financial growth machines.

This article was produced as part of Mark Minkjan and René Boer’s position as ‘critics-in-residence’ during the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2016.