The construction of the 16th-century Old Bridge in Mostar was the crowning achievement of the city. Mostar got its name from the bridge keepers, mostari, who from their towers would watch people entering the city via the bridge crossing the river Neretva (most means ‘bridge’ in the Serbo-Croatian language). The Old Bridge, designed by the Ottoman architect Mimar Hayruddin, was the symbol of the city. Mostar’s inhabitants regarded it as an old soul that connected two parts of the city together through a simple and friendly gesture. For generations it was the spot where couples would plan their first date and where the famous annual diving competitions were held. The city was the bridge, and the bridge was the city.

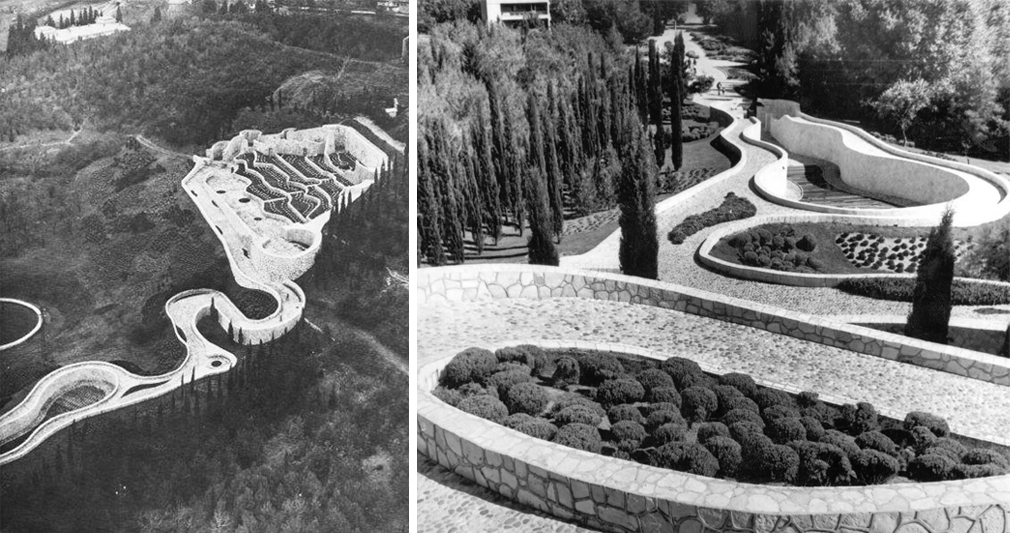

Exactly 400 years later, in 1966, the Partisan Necropolis to the west of the Neretva river was built. The monument, designed by architect Bogdan Bogdanović, is a cemetery-park commemorating 810 Partisans from Mostar. It is designed as a microcosm of the city of Mostar – a city of the dead, mirroring the city of the living. The cemetery has the same cobbled paths, alleys and gates that are so characteristic for Mostar. During the Second World War the city was known as the red city because it had a particularly strong antifascist resistance, of which the members were of Serbian, Croatian and Muslim ethnicity. Traces of this resistance can be found on the gravestones of the Partisan Necropolis, where the different names are distributed proportionally according to the percentage of the population representing each ethnicity at the time the monument was built. The monument was a public park that marked a new shared start after the Second World War.

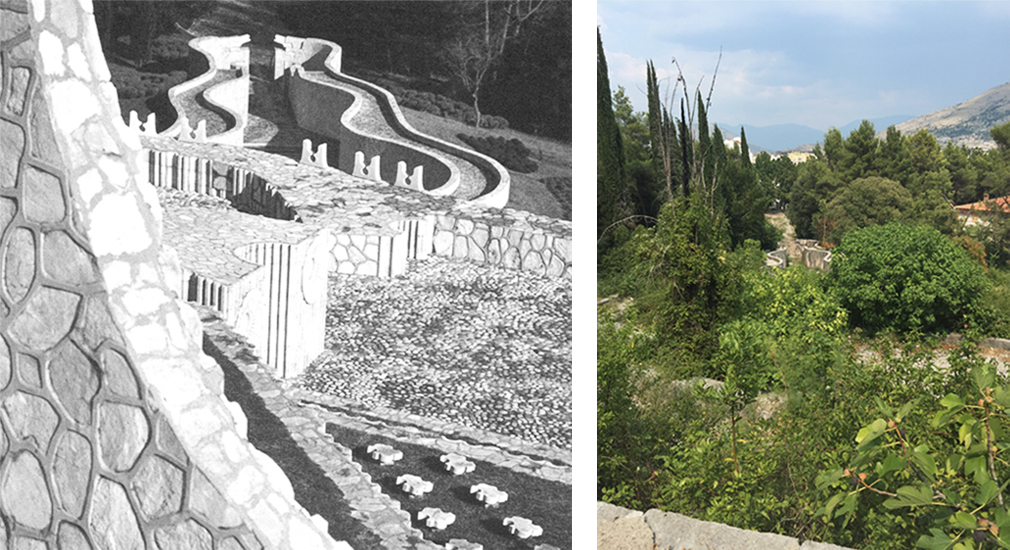

This year 50 years has passed since the construction of the Partisan Necropolis. No one could have foreseen the horrors that would happen in these 50 years. During the civil war between 1992 and 1995 seventy percent of the city was destroyed. The old friend of the city, the Old Bridge, was killed in 1993 and resurrected in 2004. Due to the city’s current extreme segregation, the connection has disappeared. The Old Bridge is no longer a connection, but rather a separation of the city. The Partisan Necropolis also got very badly damaged during the war, was restored afterwards, and subsequently demolished again by vandals. This place is now too loaded to be left alone but then again too loaded to be protected.

I visited the monument in August 2015 as an annual ritual. Every year I walk through the Old City, crossing the New Old Bridge, via the Korzo (the old promenade), past the many ruins on the ‘Spanish Square’, by the Bruce Lee monument and along the Rondo and the former House of Culture (now House of Croats), to the Partisan Necropolis. Three years ago it was already overgrown, neglected and a shady hangout. Last year I was too scared to go up into the park, the grass was too high and the entrance had been set on fire a few months before.

This time I wanted to try again, despite being warned of the dangers by many taxi drivers and friends from Mostar. It is supposed to be too dangerous as many visitors are threatened and called ‘communists’. As I visited the monument with three friends in the middle of the day in 40 degrees Celsius heat, we were almost sure no one else would be there. The place had been taken over by nature, littered with broken beer bottles, and the stones were daubed with nationalist and fascist writings. I have been able to accept many nationalist and politically loaded decisions made on public space in post-war Mostar, however the assault of the Partisan Necropolis and neglect of former Yugoslavia’s most beautiful city park is upsetting.

When Bogdan Bogdanović witnessed the severe destruction of Mostar during the last war, he wrote the text ‘The City of my Friends’ as an homage to the city. I translated his essay into English. Hopefully, this text and the images can convey my pain and the imminent disappearance of this unique piece of heritage.

Arna Mackic, 2015

Grad mojih prijatelja (The city of my friends)

Many of the memorial buildings, to which I have devoted my best mental and physical strengths, do not exist any more or are, at least for now, condemned to an invisible deterioration and disappearance. I would feel miserable if I would — even for a moment — allow myself to regret, for instance, the most opulent work of my architectural youth: the Partisan monument in Mostar, today when the real old Mostar has disappeared, along with the even older Mostarian families, whose children rest in this honourable war cemetery. When I once explained my idea for the monument, I told a grateful audience the story of how one day, and forever after, ‘two cities’ will look each other in the eyes: the city of the dead antifascist heroes, mostly young men and women, and the city of the living, for which they gave their lives…

The stone allegory of two cities did not accidentally, nor without any external encouragement, land on one of the rocky high grounds west of Mostar. The first formula was probably offered by a lecture I gave at the time. Namely, pretty vaguely, somewhere between the heaven and the earth — according to the ancient books at least — floats the city Hürqualyâ, the Sufist counterpart of the Manichaeist Terrae lucidae, which, according to gnostic speculations, was the representation of the basis for the world’s most beautiful and naive, but eternally philosophical and cosmo-poetical images. And I thought that the fallen Mostarian antifascist fighters, all still boys and girls so to say, have the right, at least symbolically, to the beauty of dreams. At the time that the monument was being built — a peaceful, quiet, bureaucratic time, with a senseless mental state and moral environment — and looking back after 20 years of war, the purity of their motives and the all-encompassing, naive self-sacrifice can only recall the memories of the tragic crusades of our children.

Contrary to the design for Jasenovac, which was for too many reasons too difficult for me, the travels to Mostar conveyed me to a totally different world of poetry and reality. For the design of the memorial in Jasenovac, the memories of former concentration camps, no matter how much I tried to flee them, were often transformed into a state of prolonged, nearly unbearable stress. The construction of the Akro-Necropolis in Mostar, on the other hand, lit a deep fire within me. I endured the not so simple and easy work without nausea or tiredness, and actually worked from my new perspective on life and death. Maybe it is too absurd to say, but it was as if I hoped that I could give some of my hidden joy to my “new friends”, whose names — Muslim, Serbian, Croatian names — lined up on the terraces of the necropolis. Their small superterranean city overlooked, as I had promised their families, the heart of the old Mostar and the then still existing bridge built by the great architect Hajrudin, once the most beautiful and daring stone bridge of the world, a divine act of the architectonic statics, in comparison to which Bogdan was just a humble builder, as one is in comparison to a supernatural appearance.

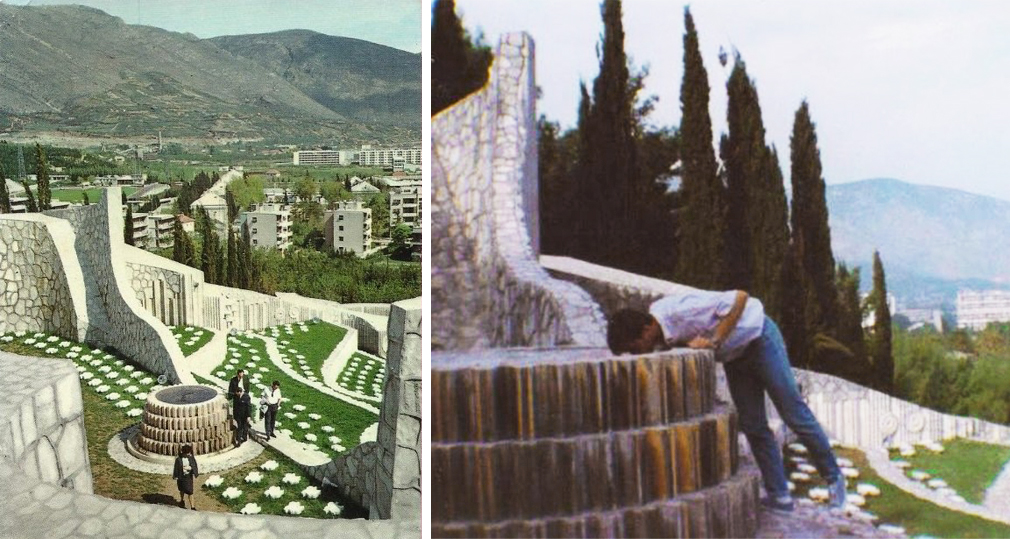

The Partisan Necropolis was a miniature Mostar, a replica of the city on the Neretva banks, its ideal diagram. However, that ideogram of the city, that hieroglyph, that stone mark was not as modest in size. It reached the contours of a modest, primeval Balkan-Hellenic acropolis. Between the entrance — the lower gate — and the fountain at the top one had to ascend an elevation of about twenty meters, and hike some three hundred meters of winding paths and hairpin turns. The road upwards was discernable by the water streaming down the stone organs towards the visitors.

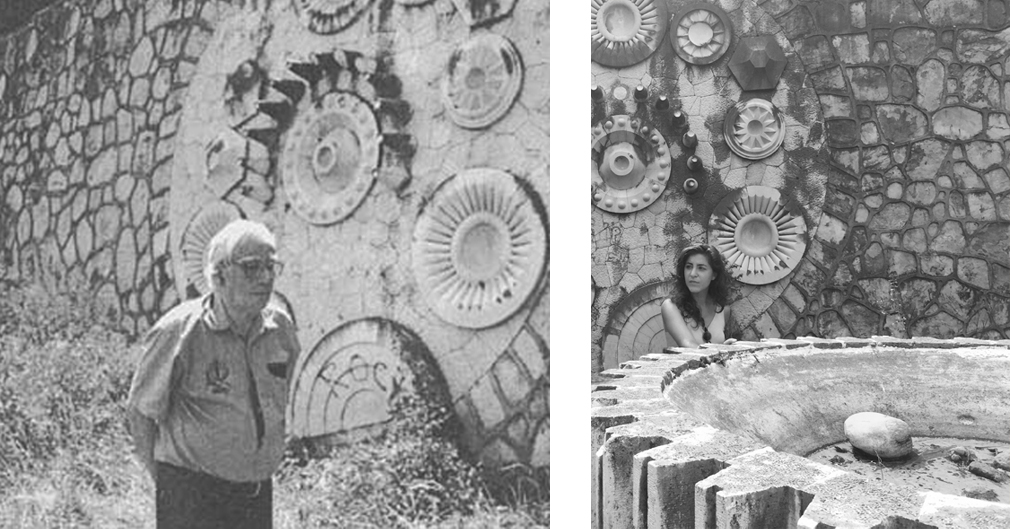

What do stonemasons who carve a city out of space and time look like? My Mostarian friends found them on the island of Korčula in Croatia and took everyone from the village who could hold a chisel or hammer. They were brought to Mostar at the end of the 1950s or in the early 60s. They were modest, polite and friendly, and they did their work religiously, almost liturgically: the resonance of their chorus-like liturgy of the chiseling took, a little interruption included, five years.

They were guided by ‘Barba’, which means uncle and grand father in their dialect; a paternal head of the fellowship; a guardian; the person that, once they return to the island, will report to the parents and fiancees who did what and how. Once Barba arrived he determined a location for the ‘quarry’, built a construction shed and made room for his working space, which resembled both a chair and a pulpit. He then ordered that the chest made out of poles, though without lid or bottom, be filled with sand and little pieces of stone, so that the piece of stone to be carved could lie softly and would not be damaged during the works. Across from his working space, directly facing him, the workers put their, somewhat smaller, chests.

Because of the heat in Herzegovina, they worked more often at night than during the day — from dawn until breakfast and from dusk till deep in the night. During the summer months, Mostar — that beautiful, and now bygone, city — and its citizens had the strong habit of waiting in the street for the coolness to emerge from the riverbed of the Neretva around midnight. Sometimes it seemed as if everybody, even children, had forgotten that one could also sleep at night. I adopted their habit — not just because I too needed the coolness to get sufficient sleep and a productive working rhythm for the following day — but also because I was playful, or rather nervous, and also even a little afraid. I had promised the inhabitants of Mostar to make something that would be unparalleled, I had driven them up to costs, I initiated a lot of work — but was I even sure that I would succeed and finish everything the way I envisioned it?

A little feverish and distracted, I repeatedly crossed the bridge of Hajrudin from the one end of the river bank to the other, over the cliff. Sometimes I got the idea that I was looking for advice from my predecessor on the problems he had encountered that always suddenly emerge when working with stone. I touched the stone balustrades and profiles and my fingers found things that during the day had been obliviously overlooked. In the dark I found connections between the stones, calcified ages ago; I felt the metal leeches and bonds, that stopped the squirting in time to safeguard the old structure from falling apart.

One night I decided to go up, to the building site. From a distance I could hear a song, a harmony of voices, a choir without words. Step by step I came closer. I looked from the sidelines, from the darkness: acetylene lamps, or maybe even lamps from the previous century, caustic light and even more caustic shadows. In this light something mysterious occurred. Barba, grey, hair electrified dispersed to the fours corners of the world, commits a crime like a magician, as the ghost of the stones. Suddenly, he lifts the hammer and the chisel up in the air, everybody lifts their hammer up in the air; they reverently keep silent, a silence takes hold of the place that reveals the voices of the night — crickets, whistling night birds, the distant sound of the Neretva. One of the masons, apparently appointed for this purpose, once again initiates a melody without words, nasal and mysterious, as in a ritual of stone worshippers. Barba picks up the rhythm with his chisel, hits the block in front of him, and starts to work the stone. The song clearly prescribes the pace and force of the hack. As soon as the melody starts to ‘rise’ (everybody is singing now), the sound of the hacks get ear-splittingly loud. Once it ‘sets’ again the hits get less intense.

Every stone sounded like a musical instrument. I knew, predictably, that different kinds of stone would resonate differently — the softer the stone, the deeper the tone. It is paradoxical, and also a bit comical, that the most solid granite whispers; that marble sings a mezzo-soprano; and chalk, the most musical stone, sings a beautiful, velvet-soft alto. Sculptors know how to perceive and even more. “Every piece sings its own song” — says one of them, in the conviction that every piece of stone is a being in itself. But when the collective hacking commences, the rhythm includes every “stone instrument” and, suddenly, every hand movement, every body posture functions in such a way that the whole orchestra serves as its own metronome at the same time. And when the hits of the tools begin to falter — a sign that the concentration is starting to drop — Barba, the spectre of the stone, unsatisfied, holds up his hammer. It is a sign that the work will be momentarily halted and that the hacks have to be harmonised from the beginning. Everybody waits for the first voice and Barba’s first hit…

The fact that it was a harmony without words, got me thinking that the ancient, proto-historical version came from times that people on the island, and on the mainland, spoke another forgotten, pre-Slovenian language. Civilisations switched, languages melted, but men had stayed the same… “Why doesn’t the song have words?”, I once asked. The replies were simple and convincing: “They’re not there, they never were!”, or “That’s how our ancestors use to sing it as well!”

The monument slowly got built, laboriously and carefully, by voluntary contributions, even also in natura (in which case the “natura” was stone), even stone of Mostarian houses, that were for the most part destroyed by time and urban planning; and families gladly donated their stone buildings. Even the quiet moving of the material, the material from the Old Town included, had a symbolic value. The stones, often with centuries old traces of smoke and calcified moss, with ‘housekeepers’ [a plant species], transported pieces of memories and the spirit of piety from one time to another, and mixed it with mighty quantities freshly masoned stone, as white as cheese.

On the highest terraces, at the inner stone walls of the “city”, in the folds of the stone walls: semi-circular niches, apsides, buttresses — squandered themselves in hundreds and hundreds of stone flowers. At least partly because of the belief in the ancient suspicion of the builder-alchemist that the mason is the child of the sun and the moon and that he therefore is so exceptionally suitable for, even destined to, the carving of heavenly phenomena, the stone flowers got abundantly mixed with the representation of the sun, the moon, planets, constellations … A place was found somewhere for the constellation of the Great Dog, which I had never been able to discern when I looked at the skies; and even for a group of stars that doesn’t even exist in the celestial carpet, but that I christened “seven slender cows” in my imagination. For those not familiar with the question these were the Vlašići [referring to the Mountain Vlasici in Bosnia-Herzegovina]. Eventually it turned out that the Partisan Necropolis as a whole recalled the grand astronomical model from which we all originate.

The lilting, heathen character of the Partisan Necropolis could not remain unnoticed. Its terraces were quickly seized by children, whose playful voices echoed in a choir amid an almost scenographic stone landscape, sometimes until deep in the night. The only thing I could still wish for is generously offered, a bit a joke, and a bit serious as well: the right to, as honorary citizen of Mostar, create a secret niche to the left of the entrance gate, to accommodate my future urn. However, it now seems like I will not be in the company of my friends that way: the gravestones have cold-bloodedly and sadistically been taken away and crushed in a stone grinder. All that is left of my original promise is that the former city of the dead and the former city of the living still look at each other, only now with empty, black and burned eyes.

Bogdan Bogdanović in Mostarska Informativna Revija MM, no. 12/13, June 1997

The historical photos in this article were found in the Facebook group ‘Partizansko spomen-groblje‘.